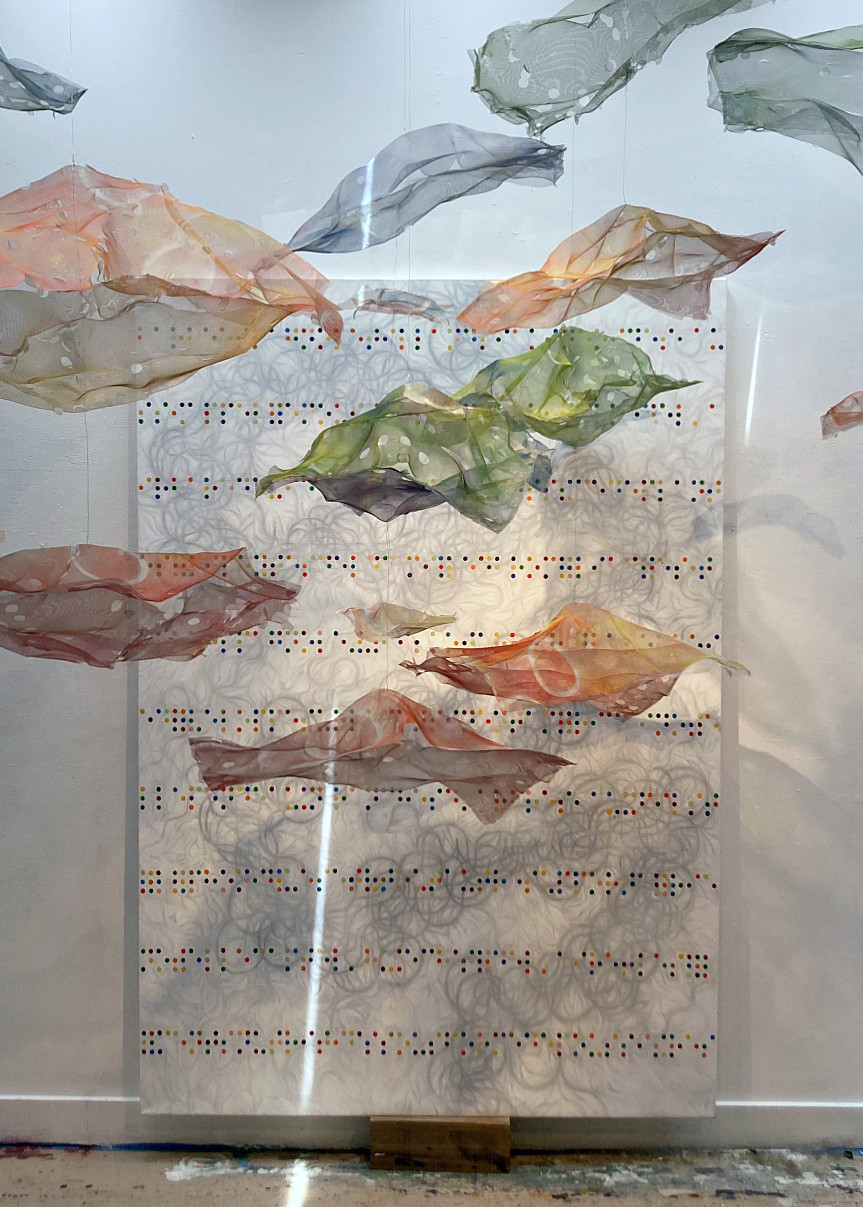

We sit below ethereal, floating orbs. The breeze in the room causes them to sway from their wired tethers to the sky. Their shadows not only mimic the soft backgrounds of a large braille and barbe espagnole painting that stands grandly behind, but evoke confusion, as the painted grey areas and the orb shadows blend into one.

Coffee is a necessary aid, as we dive into the unknown world of exploration and experimentation: two necessary components of Kenn’s process. Surrounding us are boxes of found objects and discarded food container lids, wine corks, and other items that most of us would throw away or recycle. But Kenn says he never knows when the idea will strike to incorporate these artifacts from past meals consumed. He feels like the moment is coming soon when using materials from his every day life will not only contribute to lessening the load on landfills, but utilize circles already forged – an element readily found in Kenn’s geometric, abstract work.

CONVERSATION.05

HARNESSING CHAOS

In your thought process before starting a series, a specific work, or even an experiment, where do you begin?

K: If I begin in a place of infinite possibilities, I see it all swirling around in a state of chaos. But, chaos is not just where there isn’t a sense of control, but the idea of allowing anything and everything to come in, to that process, to that practice. Then, you can pick and choose within a sense of a hierarchy, whether it’s an aesthetic hierarchy, philosophical, or whatever, and ask: “What are the important ingredients?

It sounds like you invite it all in, use intuition, formal aesthetics, and then hone in on self-created parameters for that piece, or that time of working.

K: I still think that even within a chaotic moment, maybe at times I perceive there is a loss of order, but we have to remember that even in our own chaos, we are still connected to our history – our own, personal narrative. So, there will still be some comforting, recognizable aspects of that chaos. But, that’s the part within that intentional practice: can you recognize it at that moment when something – it could be that crazy feeling when you’re so excited, and so many things are going on, how then, do you wrangle that in, within your own practice?

Sometimes I think of my brain as this continual, spiral staircase. All up and down the spiral staircase are doors, but the middle is this atrium. All of these doors are opening, and these ideas are flowing up, and through, and down. The question becomes: “When do you recognize what might be a strong point, or a jumping off point in a particular piece?”

When you work, do you have one jumping off point, and then discover, no, that’s not it, and move on to a new focus?

K: In one’s mind, or cognitive space, it’s like there’s a darkness, and then a little light flashes, like a firefly. And then, one glows over here, and then, there. It’s difficult to follow the trajectory of a single firefly. So, how do you then get the focus on that, but then it’s gone.

Right. In the night, when a firefly’s light goes out, it disappears!

K: Exactly. I kept thinking of that the other night. I was sitting outside in the dark watching these fireflies, and it made me think of cognitive synapses. The fireflies kept firing off, and I thought, “Wow, that’s my brain, right there!” And then it went dark. {laughs}

The lights are off! Nobody’s home!

{both laugh}

But, what it sounds like you’re talking about is the idea of we are all one. Our minds are not necessarily exclusive, but connected in that ether. Elizabeth Gilbert, the writer, talks about this. An idea is not “hers,” it comes through her. She once started a novel about a librarian from Wisconsin that gets sent to South America on a mission. At some point she puts the beginnings of this book on a shelf and pursues another idea. Time passes, maybe a year, and she meets another novelist at a conference. When she asks her what she has been working on, this author tells her excitedly of a book she is writing about a librarian from Wisconsin that gets sent down to South America on a mission … This solidified for Gilbert that if you don’t catch the firefly and work with it, it will fly on to offer itself up to someone else.

K: With billions of people on the planet, it makes sense that this would be possible. Oftentimes we can think about these universal connections, like our doppelgängers elsewhere. Sometimes we talk about doppelgängers as a physical presence, but we know that there are doppelgängers cognitively, philosophically, artistically, creatively, etc. They are all parsing similar categories of information. Which begs us to ask the age-old question: “How does form come into being?” This is my foundational question.

And then, “How does thought come into being, and where the hell does thought come from?” That’s probably the most pressing question in neuroscience. And, then, “Where does thought lie?”

I find that whole process intriguing and fascinating. I think that’s why I do move around in my work so often because I see these connections. And these connections are just a philosophical, visible network grid of a practice.

So when you work, it does not sound like harnessing chaos into order, or is it? Or, is it letting it just ‘be’?

K: I think it’s both, like waves on the ocean. I woke up the other morning thinking about how you can go to any beach, and waves wash up on shore. And, you can fly across that ocean, and waves will also wash up on that shore. My question is, “Where in the middle does that wave begin to go and travel to that other direction?” Does it move from the center concentrically outward? Most likely no, because other forces like winds and atmospheric conditions are affecting them. I just find this so fascinating – the ocean is just another manifestation of a brain. Not to say that it is thinking on its own, there are forces happening, and those forces react with one another. And then you can actually witness those physical forces in the form of these waves, whether they are tiny ripples, or crashing waves 20 feet high.

And it sounds like different perspectives might give you different understandings. Or, in some perspectives, you might see more chaos, and in some perspectives you might see more order. Like, if you’re on the shore and the waves are moving toward you, that’s one perspective. And then when you zoom out to find where they begin (there’s probably not just one origin), there’s a bit of a mess I imagine, of all of those waves working themselves out, deciding in which direction to move. It’s not linear, where one wave says, “I’ll see ya later, I’m heading this way,” and another wave says, “Great, then, I’ll go that way.”

But, at the shore, it seems to work itself out.

K: But don’t forget about rogue waves.

What are those?

K: Every now and then, you might have a pattern heading north, let’s say, and suddenly a rogue wave might come and head northwest. They are a rare phenomenon, but they still happen, and can cause catastrophic effects.

And now, this gets into speaking about topological surfaces. What’s affecting that from underneath? What’s affecting that force from up top? Clouds, movement, cold air, hot air. Then you have tech tonic plate shifts and volcanoes.

These floating clouds with this painting set behind them seems to illustrate what we are talking about, right?

untitled barbe espagnole with screen clouds

2021-ongoing, mixed media on canvas, 96 x 72 inches

K: Yes. So, the order can come through this. This piece integrates Braille text as the hierarchical focus. There is a pattern to the horizontal dots. But then there’s an underlying surface behind them that also begins to replicate. This is all still based on the “barbe espagnole,” the Spanish moss waving through the air that populated the Louisiana landscape of my youth.

K: Yes. So, the order can come through this. This piece integrates Braille text as the hierarchical focus. There is a pattern to the horizontal dots. But then there’s an underlying surface behind them that also begins to replicate. This is all still based on the “barbe espagnole,” the Spanish moss waving through the air that populated the Louisiana landscape of my youth.

And, when I hung it behind these screen pieces, the 2D painting and the 3D sculptures started having a conversation.

You are the instigator of what’s happening, and these things are taking a life of their own. That ephemeral nature of the shadows that these floating screen pieces cast on the painting behind – it’s both intriguing and confusing where the sculptures end and the painting begins.

K: Yes, the screen pieces are adding to that vague background in the painting. When I put the painting behind there, it was another eureka moment. You can’t tell what’s painted on – what’s real – and what’s illusion.

And right now, it’s why I think it’s so important that I leave teaching because this is now all time consuming. I’ve hit this stride after 62 years. I truly believe that it’s taken me so long to gather up so much information among all of my interests, that it’s finally coalescing. The confluence of all of these interests are truly now working in tandem. It’s as if suddenly, it makes the most sense.

Like we mentioned in the Conversation 04, when you invite an idea in and you work with it, you have your experience, but you also have no idea of what the viewer might experience.

K: True. My hope is that the viewer sees some of the chaos, order, and struggle that goes into the painting themselves. I think I am finally reaching that level, that best defines that hybridization between the 2D and 3D formations, and the further breaking down of the paintings that are now becoming sculptural, and the sculptural pieces that are becoming paintings. Thinking of a Venn diagram, where does a 3D piece intersect with a 2D painting. I keep getting that feeling that the 3D pieces are like peeling off veils of the 2D work. These layers do exist on the 2D paintings, it’s just that they are so thin as washes. But if you could, lift them off of the 2D work, you would get a glimpse that these gossamer layers, these imprints, that are really just an idea themselves. And, they are both fragile and strong simultaneously.

EXPERIMENTATION, INTERROGATION

Walk me through how experimentation comes into play with your work.

K: Let me start by showing some of my experimentations:

Here are some drawings I began, when thinking of the manipulation of space. These are all geometric with circle overlays, but with a sense of depth. And, I could see these becoming larger pieces one day, exploring that illusion of space.

Cubitum three

2005, pencil on mylar, 18 x 18 inches (on left)

Cubitum nine

2005, pencil on mylar, 18 x 18 inches (on right)

K: And here, my internal question was/is how to ‘scale up’ and replicate a large image in a numbered edition. The large pochoir expanded and opened up the process and scale of possibilities to image making within the printmaking practice, showing both the pochoir (template) and the resulting print.

K: And, this, untitled “circular reflect” explores painting & sculpture within an envelope of materiality. “circular reflect” does just that, it mirrors & reflects its surroundings along with the orange backside of the curvilinear cut-out composition.

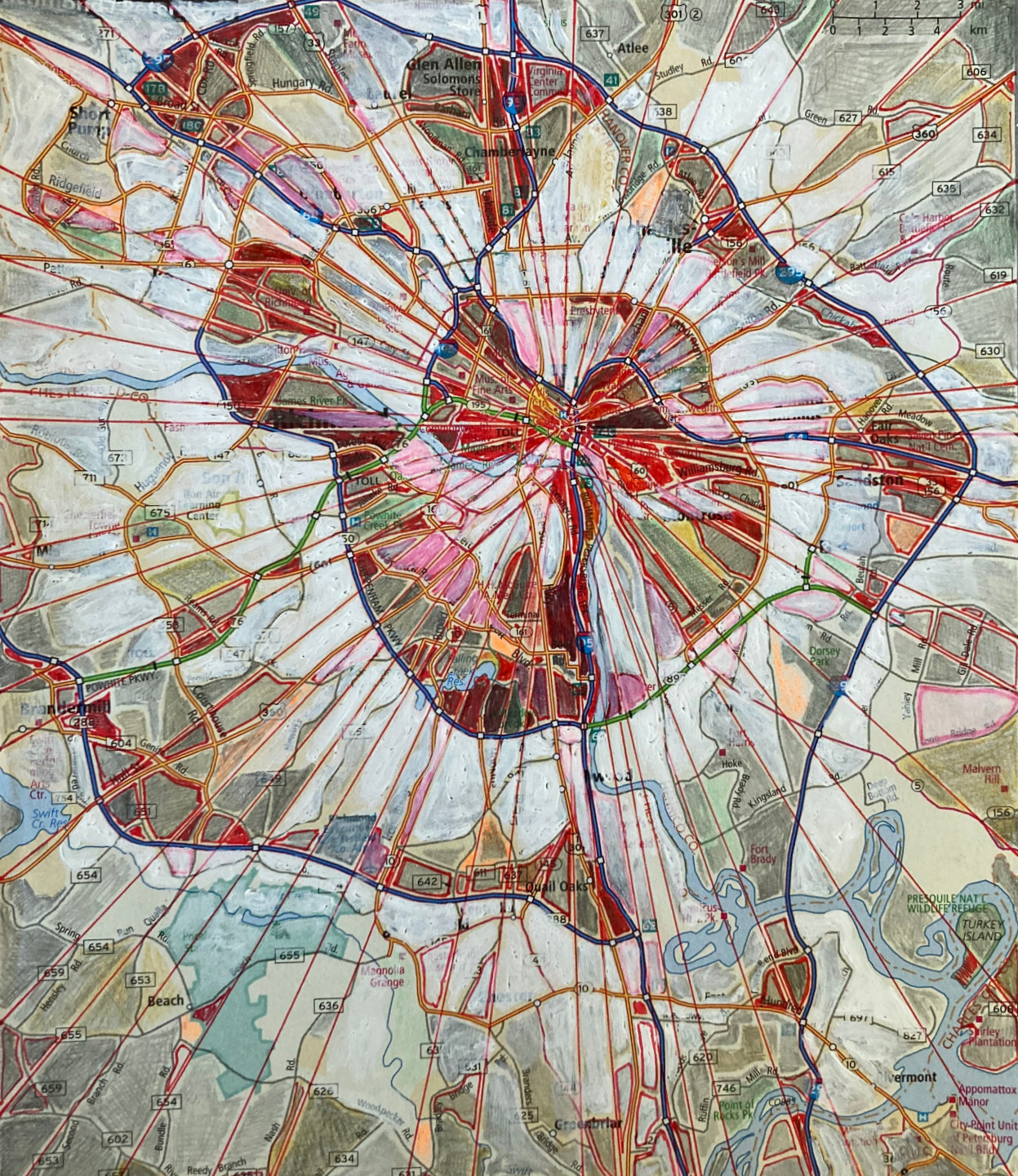

K: And, here is another experiment I have conducted with old paper city maps. We think about technology, travel, and so on. So, I started drawing on this thing with a red pen and pencil, and look how they start to take on these organic, organ-like forms.

Atlanta

pencil, pen & acrylic on found maps

This reminds me of how a fiddler from Ireland once told me that the topography of the land, dictates the tempo and accent of the music. In the northern part of Ireland, with its jutting, sheer cliffs – the music is sharp and staccato. And, in central Ireland, with its rolling hills, you find softer, swaying tunes.

Looking at your map experiments lead me to wonder, “How does this human-created construct of a city, coupled with its culture, and other influential components create this organ-like structure?” Wouldn’t it be interesting to know the details of each city to see how each organ-like structure differs from the next?

Richmond

pencil, pen & acrylic on found maps

K: And, isn’t it funny how there is that common phrase about the heartbeat or soul of a city? Because it is often all of the culture, people, strata of individuals that form and make that collective. These cities embody those personifications.

Here is an experimentation that explores the structural integrity and malleability of the metal screen material. I created truncated icosahedrons.

icosahedrons: In geometry, an icosahedron is a polyhedron with 20 faces.

In my experimentation, these forms, where the ribbing is on the exterior, I found the form to be much stronger. But, when I placed the joining seams on the interior, they were weaker, and more malleable.

It’s so fascinating, because it’s the same material, but by putting the ribbing on the exterior, it’s stronger. So, in wanting the stronger form, I’m going to have to take these other ones apart and redo them. Or, if I want them to collapse and lose the form, I can utilize this technique. So, I had to go through this process to learn the capabilities these new materials.

So, it seems, that by doing the experimentation, do you ever get metaphors for other facets of life? Brené Brown’s theory of how we are stronger the more vulnerable we can be, arose when I saw the strength that the screen forms had whose seams were exposed on their exterior.

We are always walking around in our lives with unanswered questions and unsettled feelings – you can’t help but carry those around with you. So, when you’re making something, does it resolve something else in your life?

K: When I look at these icosahedrons, I think of Buckminster Fuller, with his geodesic dome. He began to look at the comodular components that make up a whole, and how could he strengthen that? His first experiments failed miserably. But his strength came from being vulnerable and open to the outcomes, and learning from them.

K: When I look at these icosahedrons, I think of Buckminster Fuller, with his geodesic dome. He began to look at the comodular components that make up a whole, and how could he strengthen that? His first experiments failed miserably. But his strength came from being vulnerable and open to the outcomes, and learning from them.

When I work in my studio, if i stay in my comfort zone, I guess I’d still be painting still lifes à la Cézanne. But I don’t. I want to be vulnerable. I want to fail, but label it as failing, but as learning, and just part of the process.

LETTING IDEAS SIMMER FOR A BIT

K: Sometimes I look around my studio, and my studio is chaotic at times. And it makes me feel nervous. But, it’s because I also collect Items of Interest (IOI’s).

So now when I find these IOI’s, I am really concerned with this chaos of the environment. I start to ask myself, “If I don’t pick take this back to the studio, then this becomes garbage, which could affect the environment in negative ways. We now know that there are vortexes floating – hey, maybe this is where the waves begin? Maybe the waves are looking to escape this human detritus.

I have heard that there are certain beaches in the world where millions of lost objects and trash wash up on shore.

K: Right. And, now there are artists that are going to these beaches to collect this material and make pieces from them. One is, Pam Longobardi. She lives in Atlanta and we were in the same gallery, Sandler Hudson.

So, she and other artists are collecting these objects after they wash up on shore. I want to collect them before they wash out. And, be part of that solution.

So this is interesting, because I’m sure there are so many artists that think they have to recreate the wheel themselves, but you’re using something like this yogurt lid as a launch pad. It’s a continuation of a creation.

K: But using these objects here that once housed my food, it becomes a self-portrait. I’m beginning to recognize the web of this order.

Well, and your sense of belonging. A lot of times, we view garbage as separate from us – we get rid of it when we throw out the trash. But, by reusing it, it’s a self-portrait, but it’s also being totally inclusive and adopting the idea of one-ness.

K: I almost look at these as barnacles, those little sea creatures that attach themselves to objects. This of course can have an adverse effect on the hull of the ship or something. If not considered seriously, it can cause damage.

Barnacles, yes! Barnacles are also hitchhikers. They illustrate the idea of, “What’s the easiest way from point A to point B.” Barnacles say, “My job, is to just adhere to this object and it will take me where I need to go.”

K: Right. Because barnacles even attach to large whales. One of my next explorations is finding out what exactly are barnacles. I’ve seen them since day one, because I grew up in Louisiana. My grandfather had a shrimp boat. So I remember him sometimes having to pull the boats out, dry dock them, and scrape the barnacles off of the hulls.

I would be interested to hear what kind of indicator are barnacles for human-induced imbalance to the environment. Just like algae will bloom in water that has run-off from humans putting to much nitrogen on land, what kind of feedback mechanism are barnacles?

K: Right. What’s the benefit of a barnacle, what’s the drawback?

Love it! Do you have any final thoughts about experimentation, exploration, interrogation?

K: I think these found objects are a great stopping point for this conversation because they are the newest and unresolved. This idea is sitting aside. It’s still in that waiting position.

Ruminating.

K: And growing. Look at my collection: it’s growing and growing and one day I will wake up, or maybe it will be in the middle of the night, I will have that thought, “Oh – this is where this needs to go.”