K: I read books of interest, to comprehend the world at large, better understand myself, my practice and my work. Reading maintains and strengthens my capacity to articulate visual language into spoken and written language. It isn’t an easy task. Reading also adds disparate issues, information and events into my practice adding layers of synthesis. Paralleling physical exercise, when I don’t read for some time, my cognitive skills are weakened in regard to vocabulary, quotes, dates, etc. This brain fog can inhibit communication at times when clarity is required to respond to an aesthetic question. In today’s world, artists need to be educators in the public forum, especially due to the lack of arts education in America.

CONVERSATION.07

DREAM-SHAPING

Kenn, from what I know about you, to say you are an avid reader seems like an understatement, and I know you have quite a collection of books. So, where should we begin?

K: Well, the first book I’d like to mention is the biography of John James Audubon – the naturalist, the ornithologist who created The Birds of America. I was in grade school then and was so inspired by his story of how he traipsed through the woodlands, grasslands and the wetlands of America to study these birds. He actually wanted to discover and draw every bird in North America. This would have been in the mid-1800s.

My recollection is that he drew over 500 different species, and that he actually identified 25 new species, and some sub-species as well. But I think what moved me most was his passion and vision that he had. He wanted to draw these birds and then realize this book.

I have a couple of books of his. The watercolors that he drew were then translated into engravings. This, of course, became his elephant folio prints with each paper sized at 38 x 26 inches in a four volume set.

Wow! How much time did he take to create this?

K: Years and years. While he was drawing, he would then work with other people to have them engraved. He had to go to England to find someone to actually fulfill that need. Havell was the person who eventually assisted him with these engravings. After the engravings were made, they would hand color them. So these books are incredibly detailed and beautiful, and of course now, hold great value. I read that the last full volume to be sold which was about 10 years ago, sold for 11 million dollars. I would love to own a set of his books, but that’s a little out of my price range. {laughs}

John James Audubon, Great Blue Heron, 1834, hand-colored engraving & aquatint on wove paper, 39.25 x 26.25 inches

K: But, his work is so inspirational. I think about all he had to go through to document these birds. First, he went out, shot them, and brought them back to his studio and drew them. But the most fascinating thing to me was how he composed them. He didn’t just have the bird sitting on the branch looking static. Many of them were contorted to where a lot of scientists of the day questioned his authenticity. One example is of a nest of mocking birds. A rattlesnake has climbed up the branch for the eggs. The biologists at the time said, “rattlesnakes don’t climb trees.” And now, we know this to be true.

John James Audubon, Mockingbird, 1826, hand-colored engraving & aquatint on wove paper, 39.25 x 26.25 inches

K: This image of the snake, with the birds attacking it from all around – it made it into a natural, Renaissance-like composition. Instead of having these figures from Greek mythology or Biblical stories, he had this natural activity happening. I remember being so taken aback by this.

These were the first books that influenced me, and made me realize, “This is what I want to do. I want to be an artist, of that nature.”

John James Audubon, Great-footed Hawk, 1826, hand-colored engraving & aquatint on wove paper, 39.25 x 26.25 inches

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, 1603-1604, oil on canvas, 120 x 80 inches, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City (in Baroque style)

Giambattista Tiepolo, Allegory of the Planets, 1752, oil on canvas, 73 x 65.875 inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC (in Rococco style)

John James Audubon, Carolina Parrot, 1826, hand-colored engraving & aquatint on wove paper, 39.25 x 26.25 inches

LIFE-SHAKING

That’s wonderful to have that realization at such a young age. If we were to go in a sequential order, what would the second inspirational book be?

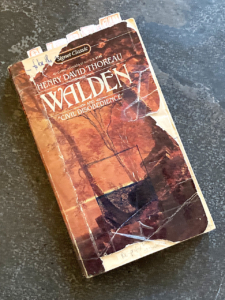

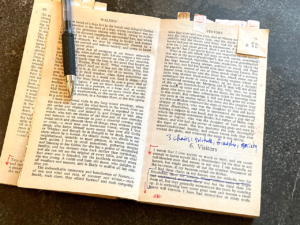

K: Well, it would have to be this tattered, torn Walden, and Civil Disobedience. My junior year in high school, I enrolled in a “block class.” When I look back now, I think it was quite forward-thinking for schools in Louisiana. We had two classrooms joined together, and two teachers. And the block class was about english literature and grammar itself.

With that combination, we would study people, and then of course, we would write. We would then evaluate, assess, and interpret the meanings behind all of this. This is where I first learned about Thoreau and Walden. And, I was completely taken aback by a person of such independence, who as a naturalist, wanted to leave society and go out and build this cabin on Walden Pond in Massachusetts.

With that combination, we would study people, and then of course, we would write. We would then evaluate, assess, and interpret the meanings behind all of this. This is where I first learned about Thoreau and Walden. And, I was completely taken aback by a person of such independence, who as a naturalist, wanted to leave society and go out and build this cabin on Walden Pond in Massachusetts.

Of course, the romantic notion of this for a sixteen year old was pretty strong and powerful. I kept thinking, “That’s exactly what I want to do.” The idea of living a simple life and removing those trappings in the conventional standards of living. Thoreau talks about different aspects of this in each chapter. Not only the flora and fauna outside of city life, but also the people that he wanted to either engage with, or not engage with.

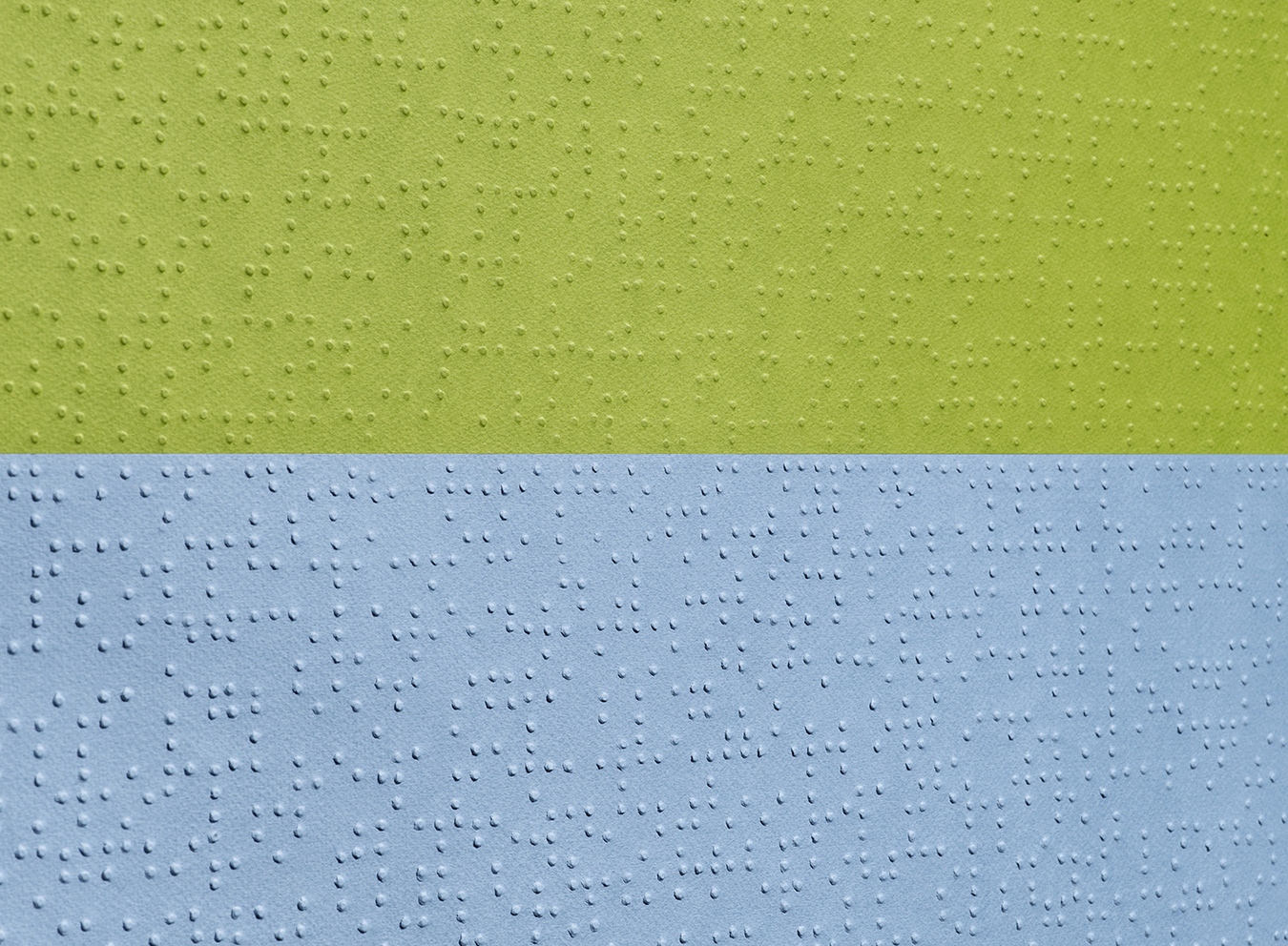

I still find myself being pulled back by this book. Subsequently, my copy of this book has all of these tabs because I created an art piece. It was based in Braille. Walden has 18 chapters, so I made 18 pieces. Ten years ago when I went back and read this again, I began to think of each chapter in terms of two blocks of colors. The idea for this arose from where he writes, “and if between the two,” where he is writing about the water’s surface, and not only seeing the reflection, but also seeing what’s underneath the water itself. Because, of course, water can be, reflective and almost mirror-like, or a window – depending upon how you look at it. Thoreau saw the pond as a window to the eye of God, or higher spirit.

I still find myself being pulled back by this book. Subsequently, my copy of this book has all of these tabs because I created an art piece. It was based in Braille. Walden has 18 chapters, so I made 18 pieces. Ten years ago when I went back and read this again, I began to think of each chapter in terms of two blocks of colors. The idea for this arose from where he writes, “and if between the two,” where he is writing about the water’s surface, and not only seeing the reflection, but also seeing what’s underneath the water itself. Because, of course, water can be, reflective and almost mirror-like, or a window – depending upon how you look at it. Thoreau saw the pond as a window to the eye of God, or higher spirit.

and if, between the two

2010-12, hammered Braille on paper, framing, latex paint, 41 x 28 x 2 inches each. “Codework” exhibition, 2012, Flanders Gallery, Raleigh, NC

That’s so interesting in contrast to Narcissist, who would only see the the water as a mirror and miss how it can serve as a portal for an expanded point of view.

K: Thoreau even went out and plumbed the entire pond. He would go out in his boat and map out the varying depths of the pond. So he was a bit of a scientist as well.

Another example of topography that seems to be a recurring theme of interest for you.

K: Also remember that the tension of water is greatest at the surface, where the water reacts to the air. When people design boats, the hardest thing to overcome is surface tension. I like this idea of surface tension, where Thoreau was probably looking at himself against the tension of society. By isolating himself from society and observing the natural environment, he gained a deeper insight about it.

One chapter of Walden, he writes about the red and black ants. The red ants were smaller, but greater in numbers, while the black ants were fewer, but larger in size. Thoreau likened the warring factions of those two to human society.

and if, between the two (detail)

and if, between the two (detail)

and if, between the two

One of these days, Walden is one of those pilgrimages I want to make. I know it’s different from when Thoreau was there, but the essence remains.

Three: and if, between the two

K: What is interesting to me about Audubon and Thoreau, is realizing the reality and myth of both of them. When I first learned of Thoreau living out in the woods, I thought of him as completely isolated and far removed from society, when in fact, he was really only a few miles from town. But, then when I put that in context to his time, traveling consisted of horse, carriage, or by foot, so the distance relevant to then would have seemed greater than that perceived of today.

He also lived off of the graciousness of other people. Ralph Waldo Emerson apparently financed him to a degree. And at one point when Thoreau was jailed for not paying his taxes, someone paid them so he could be freed. Which of course, in this book, he talks about civil disobedience, where the best government is one that least governs. When he was first jailed, he talked about being confined by four walls, but that this could not confine one’s thoughts.

When I read this as a sixteen year old, it was so timely and powerful, and led me to exert my own ideas of independence. Thinking I did not have to adhere to certain rules, I not surprisingly got pushback from my parents. But it fueled these ideas of independence, experimentation, self-discovery, and then just also being content with your surroundings.

THOUGHT-BREAKING

Okay, so we have beauty, discovery, and compositional inspiration from Audubon that made you decide to be an artist. And with Thoreau you found experimentation, observation, relocation (getting out of the fish bowl) – all helped you to question your state of being human. What would you say was the third book that inspired you, and what lessons did you learn?

K: I think the third book was The Fountainhead, by Ayn Rand. I read this as a young architecture student. This explores the polarizing views and value systems of two architects, and the contrast between the uncompromising “true artist” [Howard Roark] and the “celebrity,” [Peter Keating] who follows popular styles and will do almost anything to be successful.

Howard Roark’s mindset was that you, the recipient, had to accept the work “as is.” He reminded me of Frank Lloyd Wright, who had this huge, over-sized ego. Everything was according to Wright’s plan. He even designed things down to the plates and silverware.

This idea reminds me of the designer you mentioned in Conversation 6, Paula Scher, where she talks about the threshold that keeps an original idea for a project in tact, and how it can quickly get watered down when people outside of the artist want to add or subtract things from it.

When you look at Roark and Keating’s value systems – where one is not open to any feedback, while the other incorporates other’s ideas and makes it a collaboration – are there different benefits to behaving each way? There isn’t just one, right way, would you think?

K: Correct. For those following Roark’s line of thinking, they understand that his creation will fulfill their needs. Whereas, others will want to dictate what the creation should be.

I also read many books written about Ayn Rand because I was hungry for this philosophical conversation dealing with value. The two characters in The Fountainhead begin to value something differently, and then it explores what valuation the public sees.

A lot of that also stems from Rand’s background. She was Russian born. When she came to America, she embraced the values of liberty, freedom and celebration of the individual that so greatly contrasted with Russia’s collective communist mindset. But the more I read Rand, I felt it rested on the extreme side of individualism.

This led me to ponder the vast spectrum of the artist’s process, working solely with your own ideas, to that of a collaboration where you accept input. I realized that this way of thinking is so binary, and in reality, there are many points in between the two. You could be a person that, instead of never compromising, allows that to a certain degree. Or, if you are letting feedback or other ideas from others into your work, you will still find a bit of creative freedom, even amidst a more constrained environment.

This expanded into questioning what values, ethics, and issues are relevant to the human existence. And this led me to a strong desire to study philosophy. Unfortunately the school I attended, Louisiana Tech, did not have a philosophy program. So, I began studying this on my own.

TEACHER-MAKING

As a teacher, what books were you drawn to?

K: When I began teaching, I picked up a book, Why Art Cannot Be Taught, by James Elkins. He is a Professor in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism for the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. It is a really interesting read because he goes through the history of how art schools came about – through workshops, mentoring, the academies, and now we have these full-blown university departments, where there is a pluralism of art.

As I was teaching, I wanted to better understand that process, that pedagogy, of what does it mean to be a teacher, and how do we know that we are actually teaching someone. His book lies on the premise that we haven’t fully understood the process and the practice – especially the language – surrounding the visual arts to understand if we are teaching, or we’re not teaching.

He looks at critiques as “judicative,” where you judge certain artworks, or “descriptive,” where you describe them. So, he asks, in these two forms of critique, what do the students come away with? How does the way we language our questions about someone else’s work of art affect them?

I like the book because he really goes into the essence of the practice of making art, and asks what are the students actually creating? How are they creating art? And what are they creating it for?

This book was so instrumental in helping me understand what I was doing, or not doing, in the classroom. And, how I could possibly better that situation by creating a more positive, nurturing environment for those students. Because, I grew up in the time when a teacher would come at you in a critique not caring if they hurt your feelings or not. Many of them intended to remove the “weaker links” in the roster of students.

So, I questioned this when I began to teach, asking, “Why is it necessary for me to degrade someone else’s artwork?” I soon realized that every piece of artwork I saw in my own classroom was derivative of something that came before.

It sounds like this book was deeply influential for you as a teacher. Did your own artwork change after reading this book? Based on how you were taught, did you feel you had to unlearn messages that your teachers fed you, or teach yourself some of the concepts Elkins spoke of?

K: I think it shed a brighter light on my own practice. It validated several points, like how I see critiques as a 50/50 shot of getting anything “right.” And, that even in my own process, I realize that what I am doing is not original, but that it’s based on the conversations of people who came before me. It especially helped me in articulating my own work to a person who is not educated in the arts.

ILLUMINATING

What is a current book you are inspired by?

K: Currently, I am reading Catching the Light: The Entwined History of Light and Mind, by Arthur Zajonc. This deals with actual light, and the figurative light of the mind.

Oftentimes, I will find a book, read the abstract, and put it on a shelf until it catches my eye to read it. At times, it can sit there for a couple of years.

So, I picked this up to read when I was working on Braille pieces. Braille is all about light. It’s a tool for blind people who either don’t have the physical capacity for the light to come in and shine through their own eyes, or they’re missing something. There are people whose light diminished as they grew with age, through some type of macular disease.

This book goes into the history of light. What did our ancestors think about light and vision? He talks about the Greeks, who thought we had little fires within our eyes, which would actually send the light out, project onto our environment, and then give us the ability to see.

I’m still in the midst of reading this book, but it is fascinating how he touches on different cultures’ understanding of light.

I wonder how their value systems drove their beliefs about light.

K: Right. And, this goes back to the discussion that is illustrated in “a ribbon at a time,” about the heliocentric model, verses the geocentric one, where people thought the earth was the center of the universe. So these ideas ask, “What is the origin of light?”

a ribbon at a time

2022, mixed media on 45 canvases, 72 x 72 x 6.5 inches

K: Other parts of this are the light that opens up in our own mind and imagination, and the light that allows us to objectively see our own world. This is why I often do the Braille pieces, because they ask, “What do we see?” and, “When do we know we see it?” And, “Do our own ideologies impair us oftentimes?” You and I might see one particular event occur, but come away from it with two differing interpretations.

This brings me back to Thoreau. I love how he put himself into a different environment. He shook up what he was surrounded by, in order to see things in a new way. How often do societies do this? They have their belief systems, but do they ever change their perspective to totally question what they understand to be true?

K: Well, how many of us ask, “What is my own light?” “What does my light look like?” We don’t contemplate these issues anymore. This is partly why the books I choose to read take a long time to finish. I have to set them down to digest a passage, or new idea. I think the ills of society are directly connected to philosophical issues, and lack there of.

What would our society look like if we taught a robust art curriculum for K-12, along with philosophy courses? Values, ethics, politics, economy, etc., are all of the components we are basically fighting about right now.

Right. And, with the algorithms of social media, you are fed content that matches your belief system, thus polarizing sectors of society.

Bertrand Russell says, “The person that doesn’t read philosophy will forever be stuck in a certain dogmatic box.”

K: To lighten the mood here for a bit, I do also read fictional books. One series I am currently reading is by James Lee Burke. It’s a mystery series about this Cajun deputy sheriff, Dave Robicheaux, in Louisiana. He really speaks about the textures and phenomenological sensory components of south Louisiana – like its food, flora, and fauna. I really enjoy these stories.

Another, is Daniel Silva. His character is called Gabriel Allon, who is a master art restorer, and a sometimes Israeli secret intelligence officer. Unfortunately, he writes less about the art restoring now, but the reason he is such a good intelligence officer is because he wants to repair situations, just like he repairs works of art. These are fairly easy reads.

Howard Gardner, Five Minds for the Future, is another one I read while teaching. His book is a “visionary attempt to delineate the kinds of mental abilities (‘minds’) that will be critical to success in a 21st century landscape of accelerating change and information overload. Gardner’s five minds – disciplined, synthesizing, creating, respectful and ethical – are not personality types, but ways of thinking available to anyone who invests the time and effort to cultivate them.” {Publishers Weekly}

I would often speak about these five “minds” in my classroom, and also ask, how can you bring in other components to better facilitate your creative process? And, not only do good work, but also be a good person. So, I’ve always enjoyed Gardner’s books.

And, what would be a final book you could leave us with?

K: I think it would have to be The Geometry of Grief, by Michael Frame. It’s about a mathematician who looks at, “What is grief verses loss?.” We grieve in different ways, and it takes up different shapes and forms in our lives. I like how he languages this. Geometry is the structure that codifies space and time.

He even talks about how grief can come in the form of a singular idea. You have an idea, and suddenly it’s there in an “a-ha” moment. That moment is amazing, but then it’s gone, and you can never get it back.

I believe he had a cousin or an aunt that was very instrumental to his growth as a youth. So the grief he had over her death was the reason he wrote this book, as a tribute to her. But he also wrote it as a tribute to his own grief and how he wanted to come to understand it better. What he eventually realized, is that grief lends itself to possibility.

I think that is what books can offer. They open up new possibilities to ways of thinking and being. And for me, as an artist, this is a priceless gift.