Be prepared to walk away from this conversation with a book list of your own, to explore, collect, and read. The level of respect Kenn has for art books, along with his ability to extrapolate a myriad of meanings makes this conversation a particularly rich read.

CONVERSATION.08

ART BOOKS: TO LEARN AND BE INSPIRED BY

We learned in conversation 7 that reading is essential to your being, and having a collection of books of many kinds helps enliven concepts and continual learning for you. Not surprisingly, a large portion of these books are about art. When did you start collecting these, and what have they meant to you over time?

K: I correlate the art books with when I truly began to focus on an art practice, and what it meant to be an artist. After dropping out of architecture school, I worked a number of places, and then went back to undergrad school at the age of 28, enrolled in graphic design. I also enrolled in my first drawing class, and went to my very first art museum. So, it was the museum experience that had me thinking about books.

Although you can never replace the phenomenological reverberations of walking through a museum, the book served as an extension of the exhibits, which was vital to me since I was living so far removed from any art centers in Ruston Louisiana at Louisiana Tech. By extending the life of my visits to these museums, these books served as a portal of connection to continued study.

This was in the 80s, before the internet. An art history class consisted of a dark classroom, a slide show, and an art historian, who would just run through data, flipping through slides, whose images were often taken from these art books. Sometimes you could purchase a collection of books from a museum, but this, of course, took money. It is helpful early on in an art practice to look at other artists’ work for theory and concept. So these art books became a source for inspiration for my own work.

Every time I would visit a museum, my brain would be on fire, trying to absorb every detail.

Ah, so bringing the art books back with you served as a tool to keep those observations alive? In intense moments like these, the learnings won’t come until well after we experience them.

K: Because our practice revolves around teachers, mentors, and masters, right? So the contemporary means of practice are these museums and teachers. Well, a hundred years prior, you would go into a studio of artists, if you were good enough, and they would have you copying masters – whether they were going to the museums, or they would have plaster casts. In Ruston we didn’t have museums or plaster casts, so the book was the next means of copying the masters.

We would often take books and photo copy images, especially Renaissance drawings like Raphael, Tiepolo, and Rubens. But of course, we were also limited in that regard as to what was in the books. It was the closest thing we had. So the book became a portal, and a means to practice. I started spending more time in libraries looking at books. I checked out what books I could, but they would be due back in two weeks. Two weeks is never enough. And studios can get messy, I had to be very careful with them, so I became very respectful of these books, these objects, these carriers of information. So that’s why I started buying books.

At the onset, being an art student without extra cash in hand, I often was gifted art books.

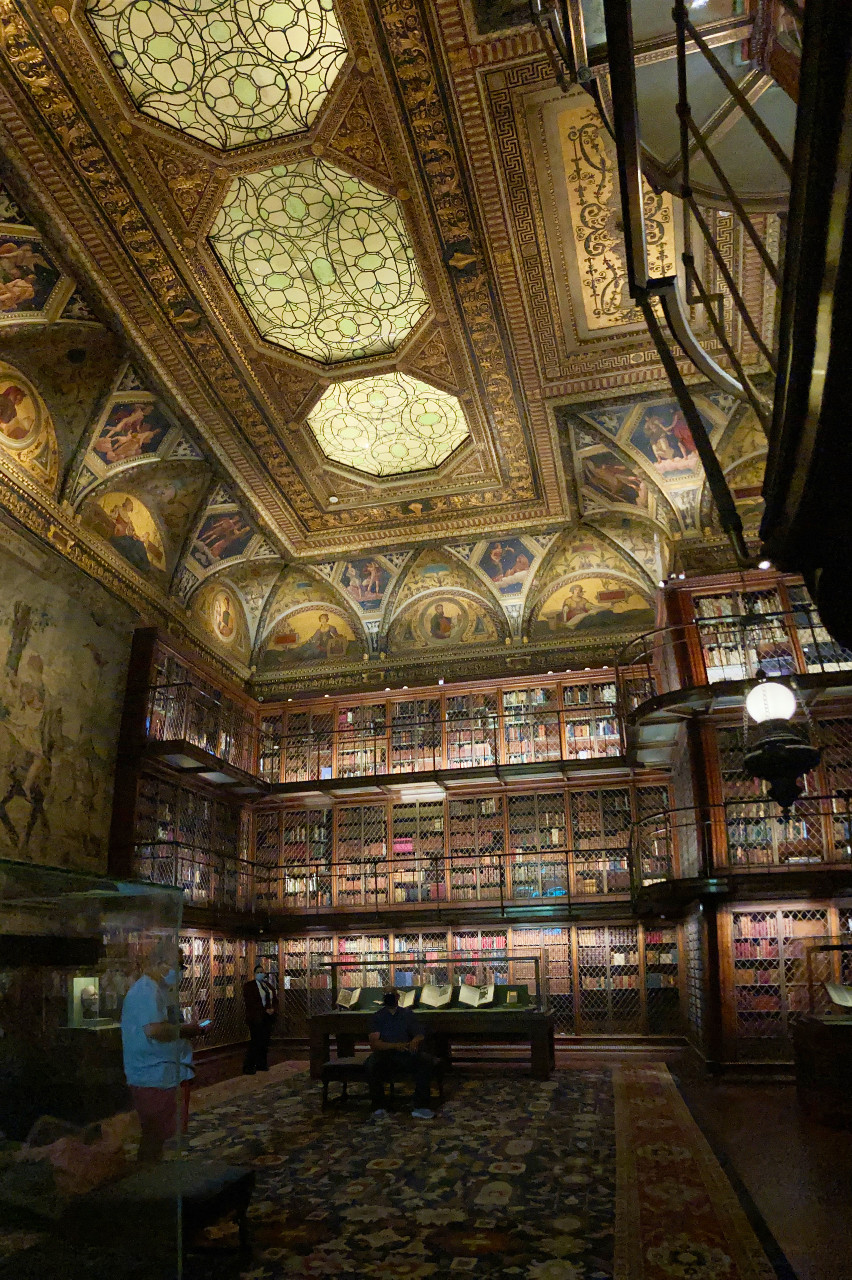

J. P. Morgan Library, New York, NY

ART BOOKS: TO EVOKE FEELING

Do you still have the first books from your collection? And now, how many do you have in all?

K: I do still have them, yes. And, now I have over 500 art books.

How do you organize this vast collection?

K: I have had to categorize them.

Oh! You have your own library, Kenn!

{both laugh}

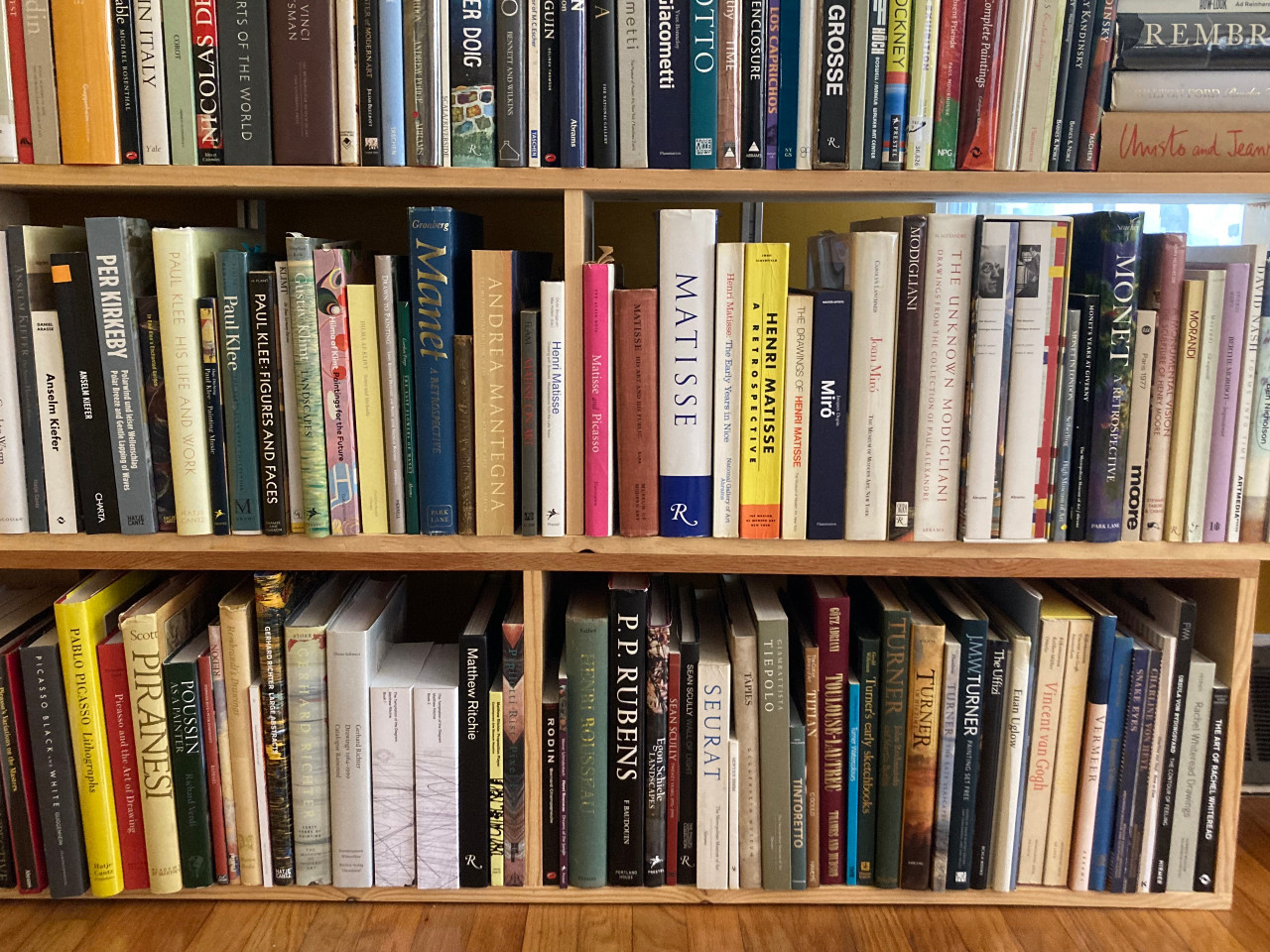

K: Yes. So I have organized the art geographically into European, American, Hispanic, Asian, and then Photography, Architecture, and Graphic Design. I also have the generalized books, which include movements, theories and criticisms. So, it’s become quite a bit.

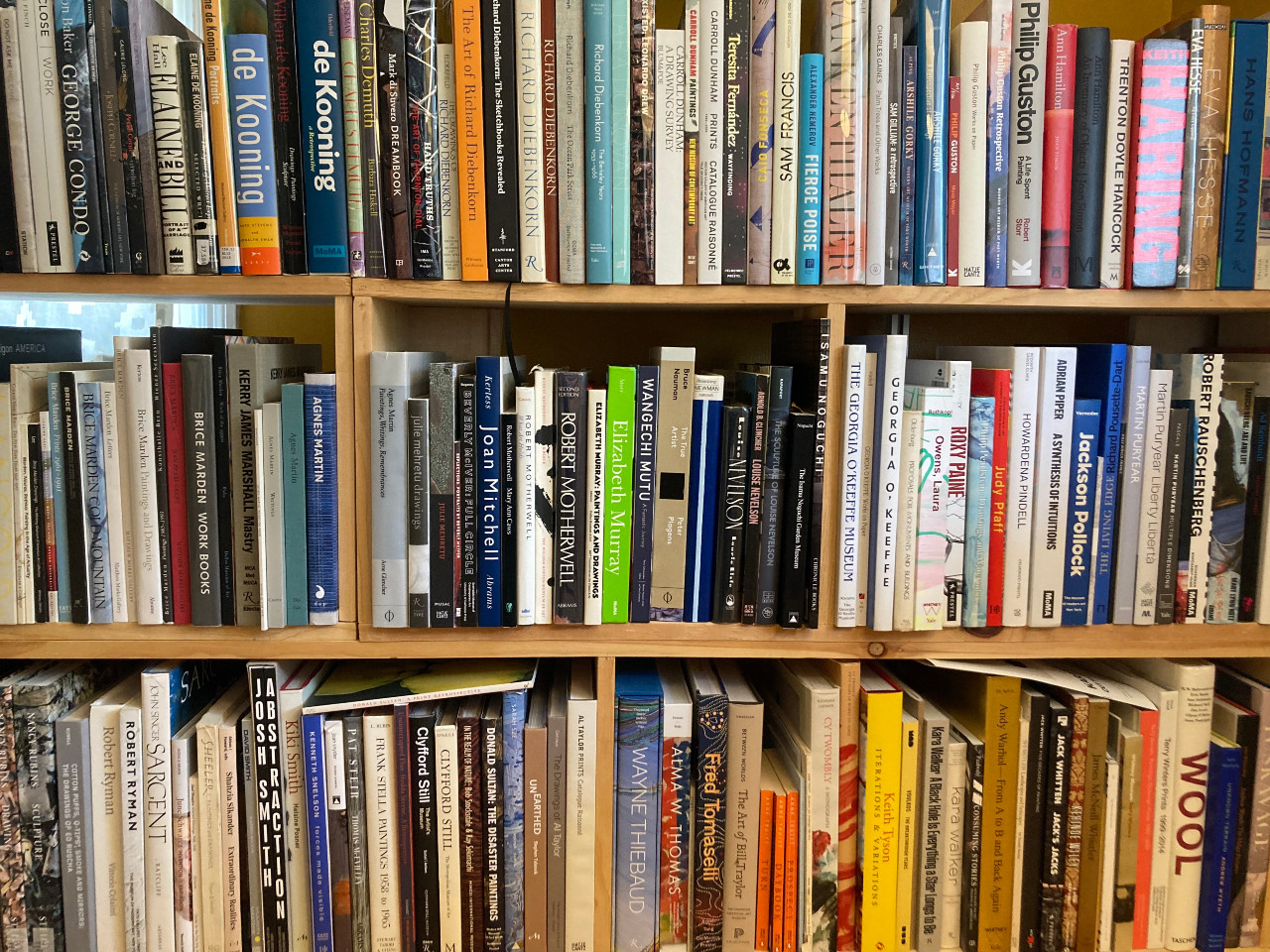

American artist section

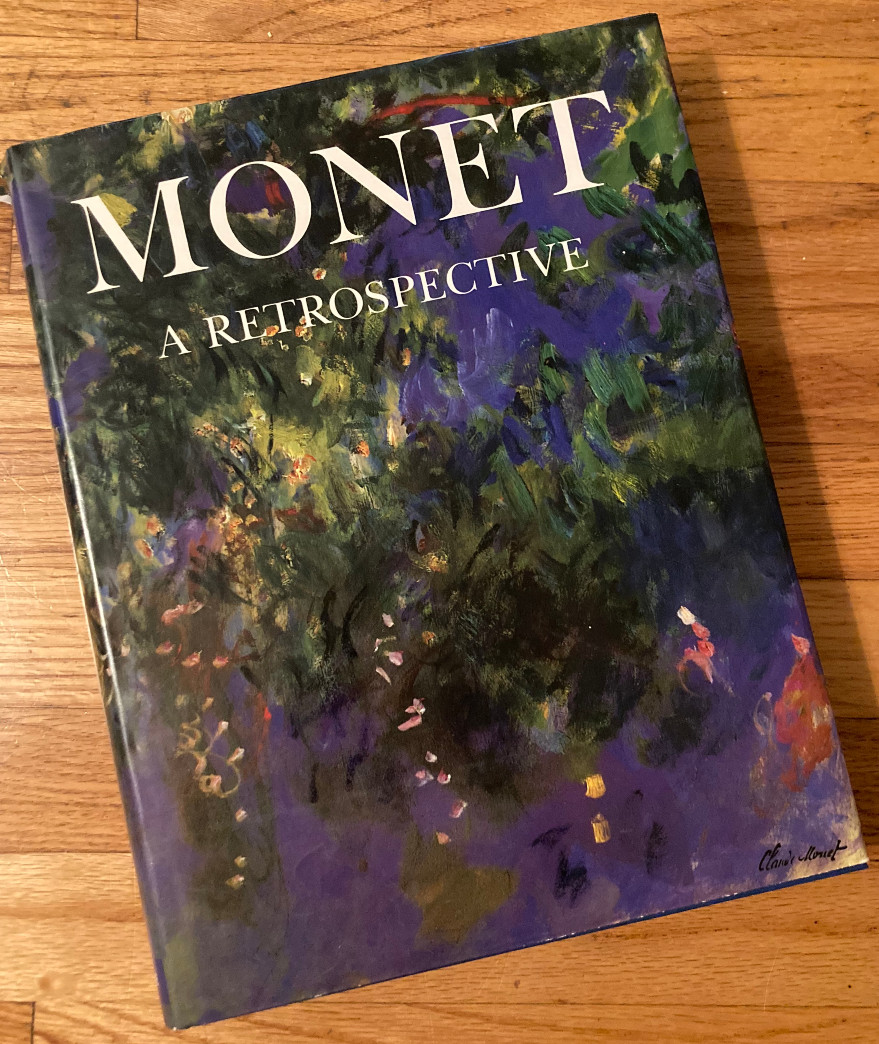

K: I now I see them as a fluid collection of ideas, but when I was first learning about art at 28, they were more stationed to their particular time and place. I would ask more specifically, “Who am I interested in learning about?” And at that time in the beginnings of my art practice, it was really the more painterly people. So, of course, I cut my teeth in Paris with the French Impressionists. At the turn of the century (1800s) it was the center of the art world before World War II. So these were the first in my collection. I think my first book was Claude Monet, with his beautiful impressionist work, that eventually progressed to more abstraction with the water lilies.

Monet: A Retrospective

K: I then collected Manet, and the American artists, such as John Singer Sargent, and Robert Henri, and so on, who oftentimes were in conversation with each other about what was going on aesthetically.

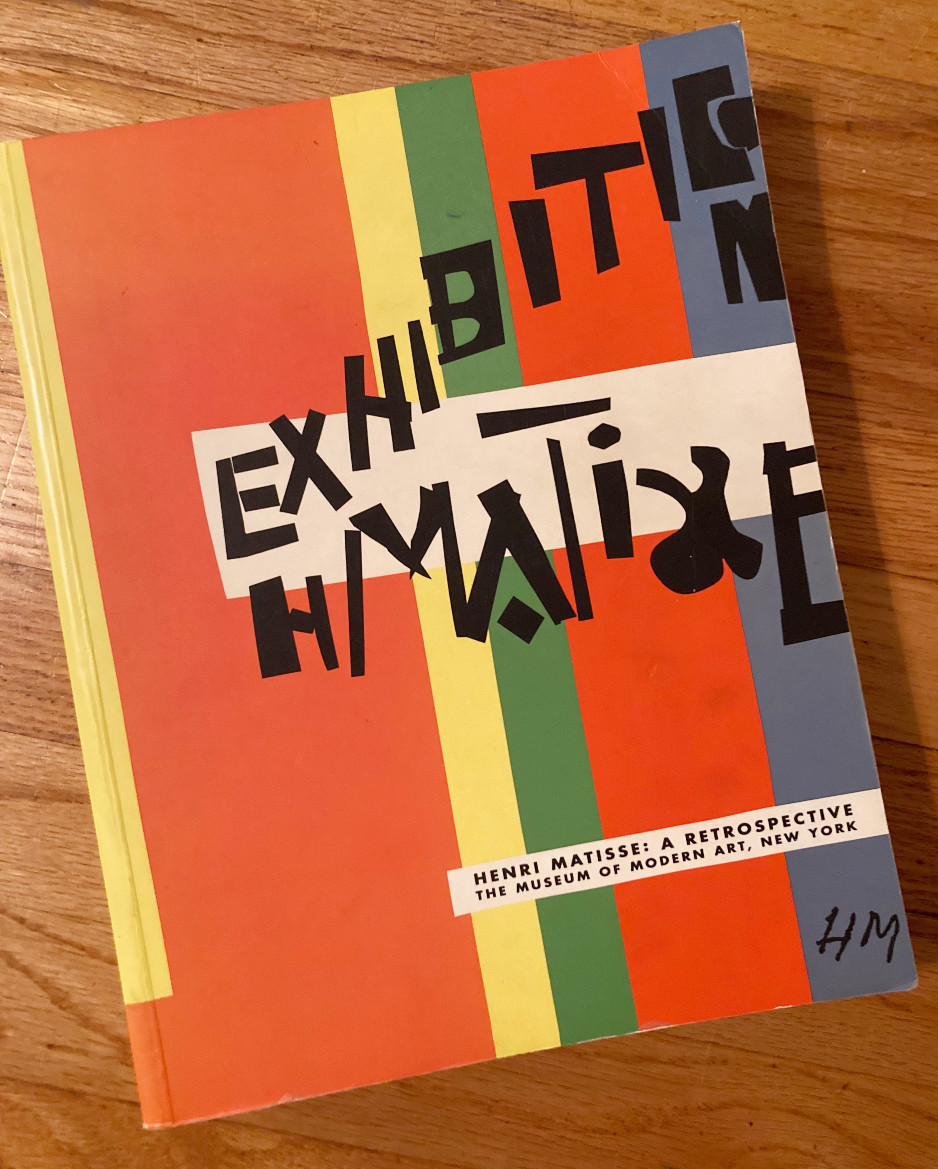

But really, the strongest influence was Cézanne. My faculty at Tech respected him because Cézanne issued in yet a different way of looking at artwork. And then I branched out between Matisse and Picasso. Picasso, of course, went out into cubism, and Matisse went into his own aesthetic of linear story telling, experimenting with line and color.

Matisse: A Retrospective, MOMA, 1992

ART BOOKS: TO PROLONG A MEANINGFUL EXPERIENCE

K: My very first large, truly blockbuster exhibition was when I was able to go to New York while I was in grad school to see the Matisse Retrospective. It was a benchmark into my own practice of looking at art. I wanted to develop every possible faculty to fully immerse myself in the experience.

A fellow art student, two faculty members and I spent the entire day there. We felt pretty cool hanging out with our professors. And when it was all over, I just wanted to bring that day back with me. So it was the art book I purchased that let me do that. Back then in the 90s, it was probably about 40 dollars. That was a lot of money for a dead-broke artist.

So the book became that carrier, or the maintenance of that information.

Yes, it extended the exhibit for you.

K: Right. We know it can never replace it, but it lets you revisit and remember that mark, or that little single dob of red against the complementary colors.

: AS ACCURATE ARCHIVE

To truly get a full understanding, we have talked about the importance of viewing art in person, verses solely in a book, or on a digital screen. Because you had that live experience at the exhibit, you were able to reference the book and allow it to trigger those real moments.

K: And still, the book is a far better measure of the work than a screen. Because, no matter how we look at artwork on a screen, there is a glass façade between the work and the viewer – a texture – that I can’t get around. The book at least comes closer as its material is paper which is closer to canvas of the actual work.

And, if you look at the printing process, the color has been corrected to replicate as closely as possible the real piece, unlike computer monitors that are all calibrated differently, so produce different color results. If you haven’t seen the work in person, discerning which image matches best becomes impossible.

K: Right, and if you Google a work of art, you will see many images pop up that all look so differently from one another, so which is the true representation? I also began appreciating these art books for the quality of how they were made. Collecting them for nearly 35 years now, the image quality and printing process have vastly improved over time. As a graphic designer, the beautiful layouts add another level of appreciation for me.

It’s great to think about all of the people involved in their creation: from the curators, photographers, and writers, to the designer who’s at the end of the line and cobbles all of this together. They are, in themselves a work of art.

: AS HISTORICAL ART IN AND OF THEMSELVES

K: Long before these modern processes, in Medieval times, the illuminated manuscript was a hand written, hand drawn form of a book. They didn’t use paper, but animal skins. This is exactly what the monks in those areas were trained to do.

We consider the first printed book the Gutenberg Bible in 1455. But, there’s now new evidence of a block printed book, The Diamond Sutra, in Asia, from the 9th century. Another interesting fact about this book is that Wang Jie who commissioned the printing of the Buddha’s sacred text, had an inscription printed in it that reads: “Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents.” This far contrasts the exclusion most experienced in western Europe in accessing the monks’ books – they were intended for only a select few.

: FOR POSTERITY

K: I hold a deep reverence for art books. The marrying of text and imagery in these art books is how the memory of that exhibition or an artist carries forward. Unfortunately, book stores and libraries don’t have the same relevance they once did. Some of us still appreciate walking into a room of books. That feeling you get when upon entering a library – you can feel the learning happening – and the smell of an old book evokes something in the mind that just can’t be explained.

: AS COLLEAGUE

How has your relationship developed with art books over time?

K: I have looked at so many books, there are so many influences, that I no longer regard one single artist or movement as a dominating influence. So, I don’t see that the books offer any inspiration for me anymore. I don’t even feel going to museums is a source of inspiration. Unlike when you are younger, you do as Picasso said, “amateur artists copy, real artists steal.” Now, the books have become these meditative moments. I pick one up and say, “I want to look at this artist, and just appreciate them for what they are doing.”

The books now extend beyond just the need to hold onto an experience. Each one I purchase has to have significant importance. Due to the cost of their materials, the extensive time it takes to reproduce the artwork accurately, and the limited number of producers, books are becoming much more expensive. And, with the internet creating a global market, books have a more universal pricing structure, much like collecting art.

: AS LOST TREASURE

K: The bookstore experience for me, is almost on par with the museum experience. When I go to these exhibits, I also hit the local bookstores. I want to see if I can scour through to potentially find that rare discovery, but also I go for the experience, the feel, that smell.

Have you ever bought a book that you already had?

K: {laughs} You would have to go and ask that. Ah, I have to say yes, on one or two occasions, I have. This leads to a whole other realm. I have so many books now, I can normally remember, but I realize I’m going to need a database or something. It has become impossible to remember everything. Now when I’m heading out to different cities, I have created a list.

Since you have purchased duplicates, it shows how much you really wanted them, and it shows how large your collection really must be. The waters are getting muddied, Kenn. But, don’t you love revisiting a book? It makes sense that you might not remember, because if say, 15 years has passed and you buy it again, think how much you have changed as an artist. You would certainly see something new in the work.

K: Well, think of rediscovering something you’ve set aside or forgotten. You say, “Now I really remember why I liked this artist and why I connected to them.” Someone like Louise Nevelson. The books can never do her work justice, because when you paint all of those pieces of wood black, you need a particular light to shine on that. Some books have come close, but to stand in front of those pieces, is irreplaceable.

I would often tell my students, “Looking at artwork on a phone, or even in a book – you wouldn’t do the same thing with food. In order to taste something as experience, you need to eat it. It’s equivalent to looking at food in a magazine.” But once again, that book is the souvenir to an experience, but at times it is for an artist that I have never seen before.

There’s an artist, Wangechi Mutu, who lives both in Africa and America. She does incredibly figurative pieces – very involved, very complex – that really connect to her culture. It’s the way that she produces these works on paper, canvases and sculptures that is just incredibly beautiful. And, I’ve never been able to see her work in person. So a book can often lead me to keep my eyes open for a when a show like hers is going to come up.

How interesting, because the majority of your experiences are going to see the work first. I wonder how this will feel for you, the moment you first get to see her work in person.

: AS MINDBENDING

K: Yes. The reciprocity, is like a circular movement. At first, when the exhibits always came first, to now the level of excitement I feel anticipating seeing work in person that I have only seen in books. It’s an exciting time. Like, I’ve seen this 5 inch x 3 inch image on a piece of paper. Now I get to see it in its true manifestation that’s 6 x 8 feet.

Oh my gosh, scale.

K: It’s just so amazing how that then feeds into it. Now, when I look at art books, it’s out of respect. It’s out of an aesthetic, internal dialogue when I look at artists’ work. Sometimes it will jog a memory, like, “Why did I like Hieronymus Bosch?” And then I look at the book and say, “Oh yeah, look at this vivid imagination and imagery of these figures!” And then, the book will spark an interest to travel to see his work, because the book will never do it justice.

Well, then there’s place. Seeing an artist’s work where they created it, or their country of origin puts it in context, unlike seeing it grouped in a museum with other artists of their time.

K: Right. Just like looking at a 200 page encyclopedia of artwork, verses a book solely dedicated to one artist. You can’t look at the first all at once. There has to be processing time.

: AS ACCESS

K: One other aspect: when my practice began to evolve from more representational into abstract. My curiosity as to, “Why am I now attracted to these abstract expressionists (the movement that began in the late 40s into the 50s?” Oftentimes, they were dealing with blocks of color, form or mark making. To fully understand this, I would look for a book of their drawings. Most of them were formally trained to a point that they could draw incredibly well. But their vision was different. The elements from their drawings could be found in their abstract pieces.

So there’s the difference: when you go to a museum, you are seeing a finished piece. The art book might have photographs of a work in progress, or these earlier drawings.

K: And then the works on paper are much more sensitive to light, so they don’t come out as often. They’re pretty much as archives in storage for that preservative act itself. The books, on the other hand, give me access to these drawings. Books give me specialized focus, like now I have a book of just Van Gogh drawings – not just his charcoal, but some of his reed and ink he was using in the south of France. It’s rare to see these in person. It would have to be a blockbuster event, in a dimly lit gallery, to those actual works. The media they were using is very fugitive and will fade over time.

The illuminated manuscripts. The watercolor drawings of Audubon. The New York Historical Society owns them. Five, maybe ten years back, they started pulling these out some of those watercolors of the birds. I said, “I just have to get up there to see that.” But I couldn’t, unfortunately. It’s one of those things I keep my eye on so I can see it the next time. But in the mean time, I have the book.

Katherine Grosse book with die-cut cardboard slip-cover

: AS EXPERIENCE

K: Artists are now seeing that they are producing art books, where they are less about joining together scholarly texts, reviews and images, but more about the experience itself. Katharina Grosse is a German painter, and she uses a spray gun. She will spray these huge installations on houses and elsewhere. I have seen a few of them before. I was curious what she did painterly-wise. I saw an exhibit of hers in New York. You could see she used a spray gun on some of the areas of the paintings, but other areas were so well defined. She was using these stencils. I bought the book from the exhibit. The book came in a slip cover as a stencil cut out on the cover. Talk about adding to that texture of the experience.

It was an invitation for you.

: AS INNOVATION

K: I have used this book as an example to my design students asking, “What options do we have besides placing images and text between these hard covers? Can the book be reinvented in a certain way?” When creativity is utilized in book making, it can jar someone’s experience, and make it unforgettable. Some have these extensive foldouts because that is the only way to show the artwork. It is these details of the art books that I truly appreciate.

: AS MEGAPHONE

What is the most recent art book you’ve collected?

K: I went to the Asheville Art Museum last night to see a new exhibition with Richard Misrach, and Guillermo Galindo. Here’s the description:

“Border Cantos | Sonic Border is a unique collaboration between American photographer Richard Misrach and Mexican American sculptor and composer Guillermo Galindo, using the power of art to explore and humanize the complex issues surrounding the Mexican-American border through a transformative and multi-sensory experience.” The exhibit runs June 22nd – October 24th.

It’s incredible. The two artists met when Misrach was photographing the border. He started seeing these pop-up pieces of art. He didn’t know if they served as signs or symbols for the immigrants. While, Galindo was collecting leftover detritus from the immigrants and making musical instruments from them.

In the exhibit, there are pedestals, each having their own sound system. Each one will play for a while, then another will start playing, and then another. And as you are looking at the oversized photographs of scenes from the border – what an astounding experience.

And, of course, there’s a book that goes along with the exhibition. I found it so poignant, and feel so strongly about what is happening there, I brought the book home to return to again.

Ah, that sounds amazing. I’ll have to go. And, you have a painting in the museum as well, correct?

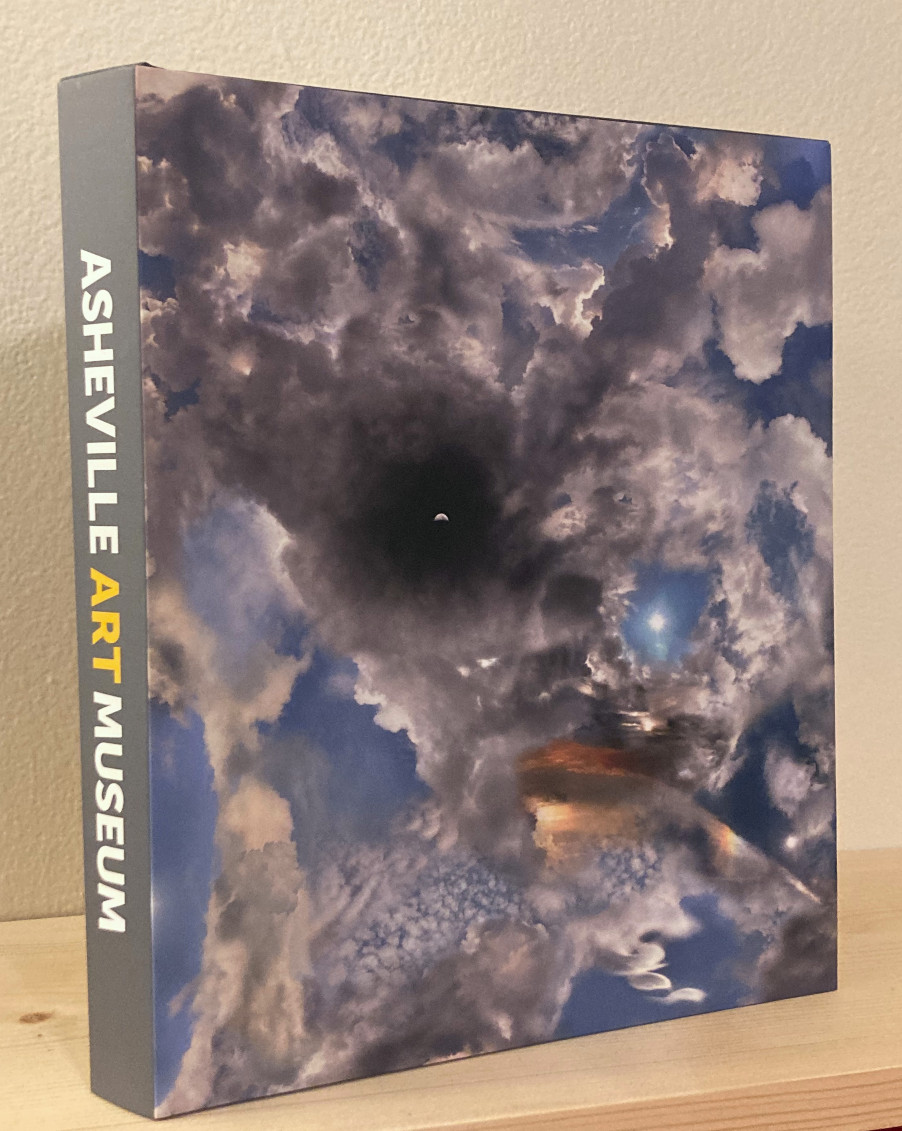

K: Yes, I do. So that leads to another category in my collection. Including all of these books of other artists I’m looking at, now, I have another collection of books that my work is also included in, like museum exhibitions. Recently the Asheville Art Museum just released a hard cover book of their collection. One of my paintings is included in that. I had no idea that they were even doing that. So, when I was at the museum, I saw the book, and secretly thumbed through and there I was.

So, did you buy the book?

K: Oh, hell yes!

{both laugh}

Asheville Art Museum: An Introduction to the Collection, 2021

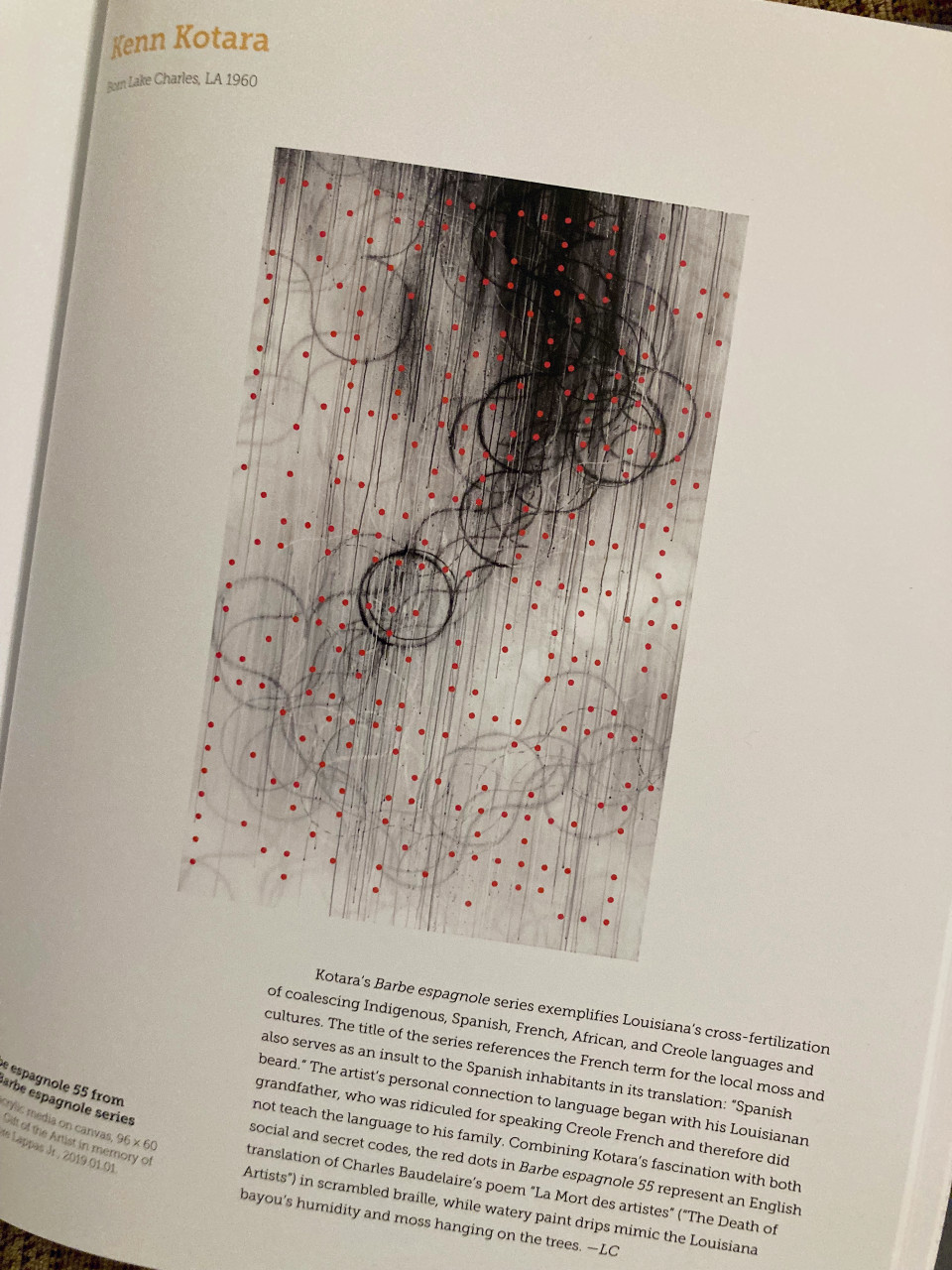

Kenn Kotara, Barbe espagnole 55, 2012, mixed media on canvas, 96×60 inches. Collection Asheville Art Museum

European artist section

: AS PLACE, AND RITUAL

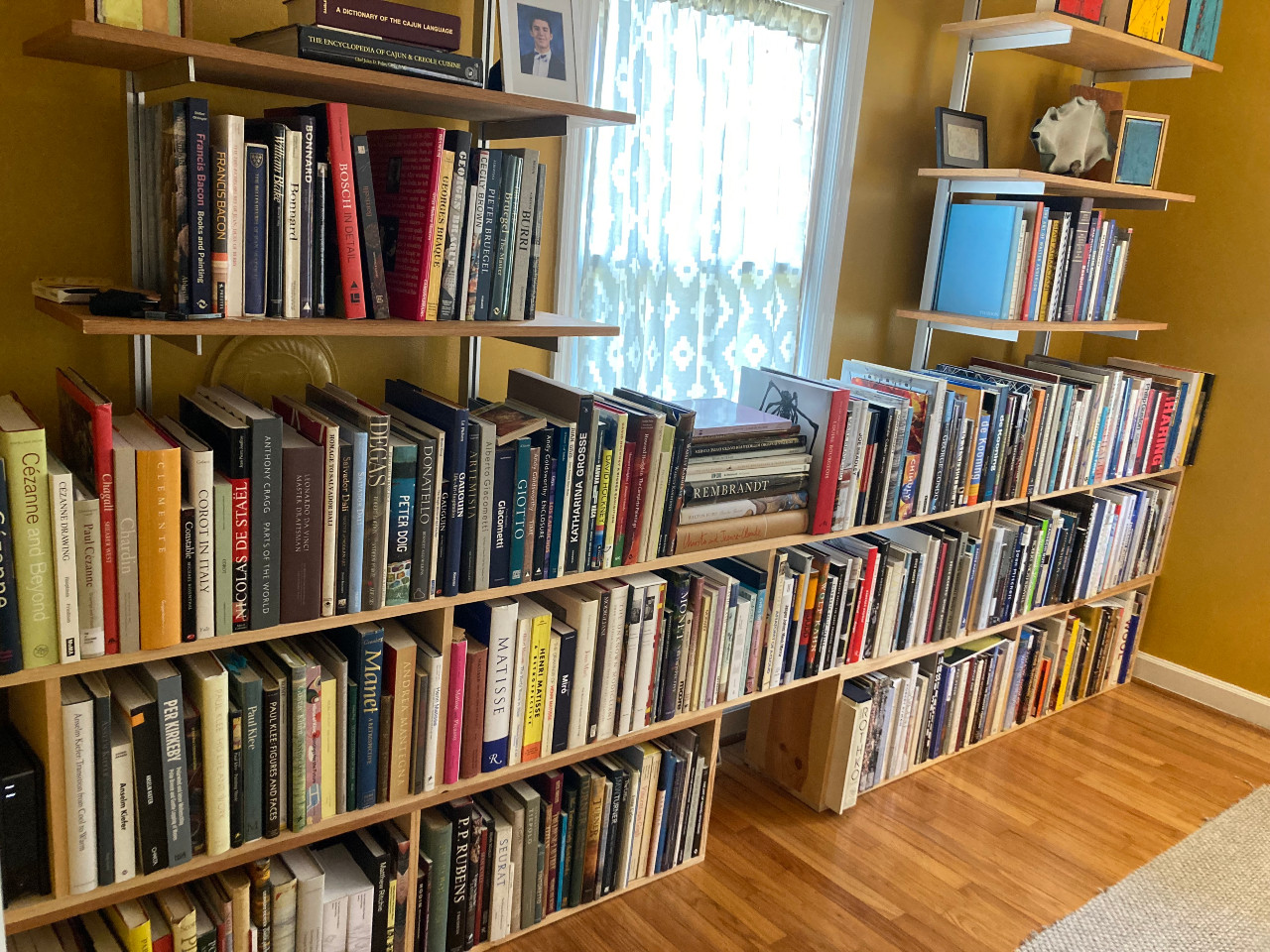

Where are your books? Are they in a place where you can go, sit in that room, and be with them? When you read one of the books, are the other ones around you?

K: What a great question, and yes. They are in my living room because, one, that is the largest space I have. Just the European and American books occupy a wall unto themselves.

Did you build the shelving for them?

K: I did. And the space keeps growing. {laughs}

That sounds like an installation in and of itself. When I think of them visually, the spines of the books are what show – you don’t display a collection like that with the covers. So, aesthetically, how are affected? And, how do you feel towards them?

K: It’s become comforting to go and sit with those books. I don’t know if I can pinpoint a singular feeling, but they offer easement, in a familial way. Oftentimes I feel like I am standing on the shoulders of these giants that came before me. Some are also contemporary, and most are people I don’t know. But it’s comforting to know that the creative spirit is there, and that I have access to them at my fingertips, as opposed to going on online. That’s much more satisfying intellectually than perusing through images online. I would often stress this to my students: go to the library. Find the book.

Kotara Library of art books

Walk us through the experience of reading one of your art books.

K: Something about morning, and morning light, with a book in my lap, resonates more so than any other time of the day. So, where I sit to read, depends on the light. My mind is always hyper alert at this time of day, ready to absorb meaning. Having one of these books speak to me first thing, often sets the tone for the day.

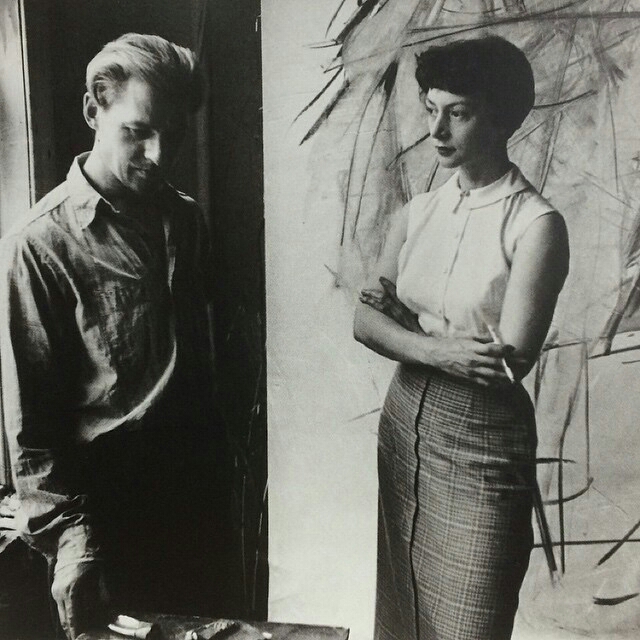

Bille & Elaine Dekooning, 1950’s, photo Rudolph Burckhaldt

: AS A WINDOW

We have talked extensively about the art in the art books. What in particular do you enjoy reading about the artists themselves?

K: I love seeing the photographs of the artists, in social settings, in their studio, or with other artists, often in black and white. That, I find interesting. A few years ago I went through this Elaine deKooning phase, along with other women from the Abstract Expressionist era. They were often considered secondary, and who are getting their due now.

So I’m reading this book about Elaine deKooning, and there’s this photograph of her and Bill deKooning in their studio. I get a chuckle because here they are in his studio, and you can see his work in the background. His mark making was, I don’t want to say aggressive, but it had that kind of attack to it. And yet in this photograph, they are both dressed so nicely. It made me think, “What a different era.” These art books have the capacity to mark such a moment in time. I really love that.