Kenn approached his teaching career in the same way he approaches a painting: researching, observing, immersing himself in process, and questioning everything. The common expectation that graduate students would go on to be teachers, despite the fact that not a class on how to teach could be found, opened the doors of exploration for Kenn. Through this, what he found was that teaching and learning are everywhere – even in the most surprising places.

CONVERSATION.10

AN INVITATION

What was the impetus for you to become a teacher?

K: During my review in the last year of graduate school, I remember I was asked if I wanted to teach. I was teaching as a TA then. I was the only one of about a dozen graduate students that told them I wasn’t planning on teaching. When they asked why, I said, “I don’t feel I know enough to teach. I think I’m still in my own educational process. I’m still learning.”

Over some time, I was asked again to teach. UNCA approached me to teach a Basic Foundations course. I had met a couple of professors, and had submitted my work there for possible exhibition. I accepted the offer because I realized I had something to offer – my experience. By this time, I had exhibited and sold work. I had a studio, and a practice. I finally felt confident to walk into a classroom to speak to young people about this thing called “art.” Why do we do it? What’s it for? Who do we do it for: is it for us? Someone else?

BACK TO BASICS

K: I took all of my formalist training, and where once I would absorb it, I could now disseminate this. I appreciated that class as a foundations course. For me, it was a way to go back and think about the foundations of the elements of art: light, shape, color, value, and the principles of design – because this was exactly what I was teaching.

From there, I got a call to teach at A-B Tech College. We still had our graphic design business. Quickly, the teaching began to have a higher priority than graphic design because I enjoyed teaching the studio courses. Then, A-B Tech hired me full time to design a two year Graphic Design program for an Associates Degree. I taught there several years full time.

What did you enjoy about teaching?

K: I really enjoyed the idea of design, but also synthesizing disparate issues from the art world. Designers don’t work in a vacuum, so we needed to look at designers culturally, anthropologically, and so on.

Concurrently though, my studio practice was developing quickly. I was increasing my inventory and exhibiting more frequently. This was right before the recession of ’07/’08. Everyone was developing. Corporate clients were calling left and right. I realized I couldn’t do both. So I gave up teaching for a few years.

RENEWED PURPOSE

K: But then, the recession came. I had a son. It was time to pause and take stock. Having a young son had enlivened the teacher within me. Serendipitously, I was approached to teach again by Mars Hill University. So I taught there for five years part time as an adjunct, I just recently completed my sixth year of teaching full time, and officially retired from teaching this past spring.

MHU art class field trip

What did you find was the value of teaching?

K: Teaching is so important. Especially from people who have lived what they are teaching. I remember when I was in grad school seeing there were teachers who stayed current in their field by working alongside teaching, and there were those who solely taught. There was a vast difference between the two.

CARVING OUT A STYLE OF HIS OWN

Do some teachers get stuck in a time zone of their own education?

K: Yes. And compassionately, it’s easy to do that. So it incentivized me to change it up every semester when I taught. Of course the curriculum is set, but the faculty in our department would look at curriculum mapping: how do these students maneuver through first, second, third and fourth years, and hopefully get to the level of undergraduate mastery. But within our own courses we had the freedom to manipulate them according to what we deemed pertinent at that time.

And, of course, you were also a practicing artist at that time as well.

K: Correct. And that was part of my pedagogy: to incorporate my studio practice into my teaching practice. And one of the reasons I eventually quit teaching Graphic Design (at which time we were converting to “Graphic Communications”) is because it is such a different animal now than when I went into it in the 80s. It was all about print back then, and now it’s about UI, UX, the experience, social media content-driven, etc. I no longer recognized my own profession.

INCORPORATING REAL LIFE PROBLEMS

K: It is important to relay antidotal experiences to students. They will be immersed in solving a problem, and you can share, “That reminds me of the time when we did this or did that.” This gives them relatable context for their problem so they can see their connection to other artists or designers. Then they can understand that they are not unique in what they are doing. It’s been done before.

I liked the process of the Q&A where you ask, “How do you begin conceptually, abstractly, and end up with something that is concrete?” This teaches them about process. It starts with defining the problem at hand. But I always encouraged them to not jump into a solution. Rather, if you think you have an idea, put it aside. Then go through the process of what I call “The Brief.” You start with defining the problem, specifically, as to how you understand it to be. I would never give my students paper handouts. In a design or studio practice, you do not have a boss handing you a prospectus and a detailed outline of the problem. They are verbalizing this, so I thought it was pertinent to develop this skill. And, after the problem has been defined, if anything is missing, you must recognize it immediately.

So to begin with, I would give them as little information as possible, so they could identify the missing information. I wanted them to be able to sit with it, and develop a process of questioning that would give them everything they needed before they started the design process. With this methodology, the students began to be engaged. After they had all of the information they needed, they would re-write The Brief.

It was then time to begin researching. I encouraged them not to assume anything. Define as many parameters as you can before moving on to creating a concept or ideation. So many times a student would raise their hand too early in the process and say, “I have an idea!” And I would tell them, “I don’t want to hear it. It’s not time yet. Just like in a math class, I want to see the work on the side before you come up with the answer.”

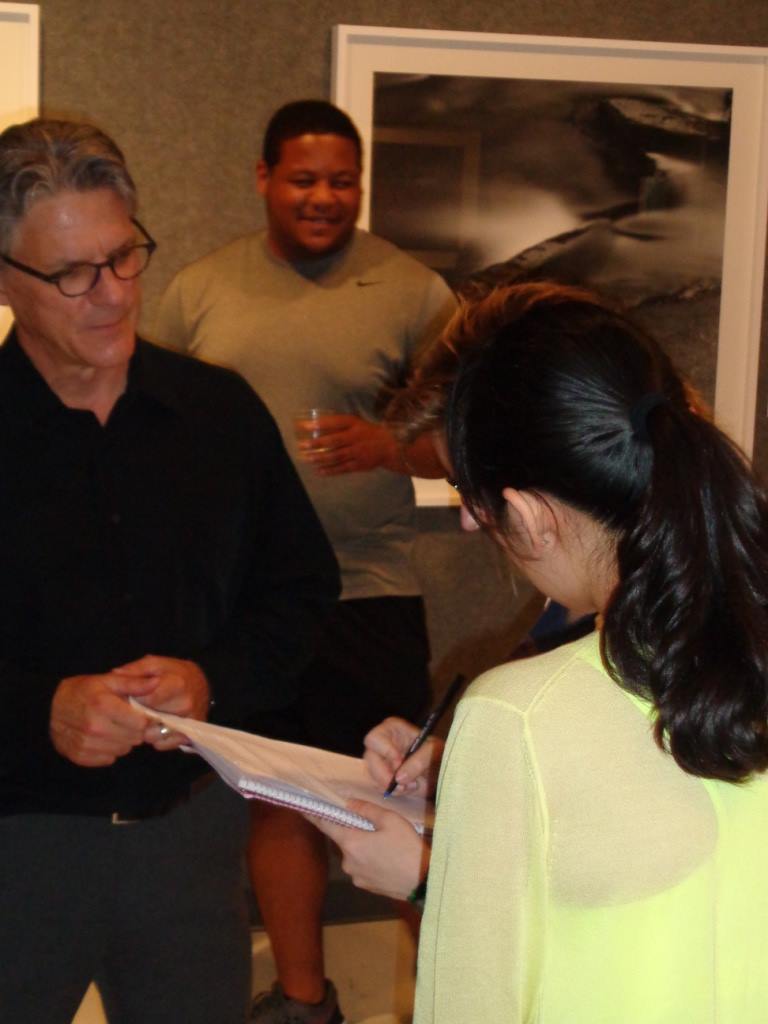

Conversing with student Weizenblatt Gallery, MHU

Yes. This helps them develop a rich context behind the idea, instead of just coming up with something that will look pretty.

K: This is not to say that you can’t come up with an immediate idea. Just hold on to it. In “The Brief” you are going step by step, checking on the one before. You are always looping back. The process is fluid. And then, eventually you can look at that idea and see if it still holds up, or if something else would be a better solution.

TEACHING AN EXPANSIVE MINDSET

K: The idea of working with collegiate-level students in creative thinking, problem solving, communication (both written and oral) are so needed. What I would also bring into teaching was the big picture, the philosophical perspective. The methodology I used was to not simply answer a question they asked, but to meet it with yet another question. That would oftentimes frustrate people. At first they wouldn’t see that what I was trying to do was to get to the crux of what they were asking. But, once the frustration lifted, they understood the power they had to solve a problem.

That sounds like a timeless format. It’s interesting for you to be a student in a certain pocket of time. You could reference the masters that you were studying. But then, to teach at a different time in society, I would imagine the values of the kids you were teaching were different than those you held as a student. But yet, is there a timelessness of what is needed by any student?

K: There are paradigm shifts occurring in education all the time. Technology is one of the drivers. Cultural influences – whether they are political or economical are also at play. Current job opportunities also dictate context to the curriculum. Most people have the idea that they are going to get a degree to then have a well-paying job.

Now, in the arts, graphic design has been that core area where after graduating, you can immediately get a job. But with a painter, or sculptor, you are on your own.

What parts of your education did you then give back to your students? Yes, we have to do things differently as times change. But what juggling act did you do in your creation as a teacher? What did you draw upon that worked for you as a student? And, then how did you tailor it to be relevant to this time?

DISCOVERING A STYLE OF TEACHING

K: When I was going into my first teaching experience as a TA, I met with my graduate advisor. He told me what my role was to be, gave me the syllabus, etc. I then asked him what advice he would give me having never taught before. He told me to adopt a tough love mentality. He said you must be firm with them. If someone gives you trouble in class, you come down hard on them and make an example of them so that everyone in the class knows where you stand.

I took this advice, but when I started teaching at UNCA and A-B Tech, I remember I was relying on that little experience. At the time I was in graduate school, even though we were grooming people to be teachers, I never took any type of educational course. I knew nothing about the educational process beyond my own drawing from aesthetic experience.

So after a couple of years, I moved away from the tough love teaching methodology to one of compassion and understanding. I moved more towards empathy, equality. Although still realizing this is a teacher/student relationship. I’m not here to be your friend. But, I began to turn around the critiques to make them about something positive in someone’s work. If they were sincere and authentic in their practice, I would recognize them for that. Even if they weren’t the best drawer or painting person there. Now, I would come down hard on someone if I saw that they were trying to skate through this and say, “I just don’t think you are trying hard enough.”

So you held people accountable.

K: Exactly. So that shift changed for me. I realized what I was taught by my own faculty members, worked for them, but it doesn’t work for me.

SEEING THINGS A NEW WAY

That is the same in your own practice – you use something as a launching pad, and then you make it your own.

K: Yes. Oh, here’s a fun little side bit. I recall the teachers asking when I was a student, “What is your favorite piece, and which one do you like the least?” We would be having a critique and there would be a dozen drawings displayed. And whatever I chose as my favorite, would oftentimes be the faculty’s least favorite. And whatever I considered my least favorite, would be their favorite. It happened time and time again.

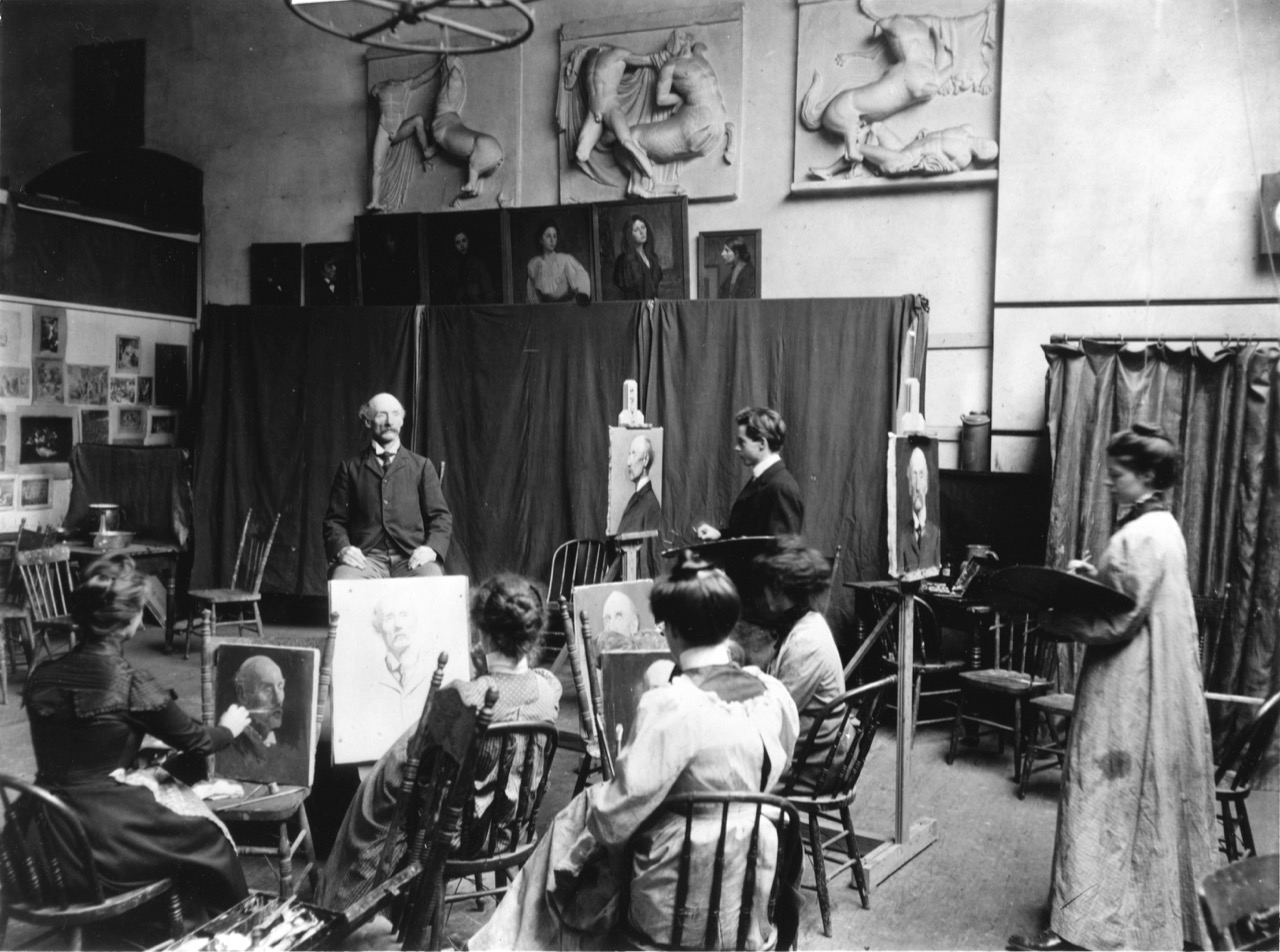

Historical photo of figure painting class

As a teacher when I started doing that – the exact same thing happened. I wondered – how did this happen? What I began to recognize is that through experience, we talked about comfort zones within our own practice. We talked about working on a piece, struggling through the process, and the piece almost becomes too labored – too thought out. While another piece – maybe they hadn’t spent as much time on it. Maybe it was more about mark-making. There was a rawness, or you could see more depth into it. So this dichotomy began to become clear.

So now you have collected experience as both a student and a teacher. With your vantage point as a teacher, are you able to discern what motivates a student? Like, if they are motivated extrinsically by getting a good grade, verses intrinsically where they strive to truly learn and create something authentically?

K: Well, this goes into the entire process. When having that one on one with a student, oftentimes I would ask, “Bring all of your work with you. Where’s your brief? Where’s your research? Where are the concepts leading up to this?” That was a tell-tale sign. If they didn’t have it, they usually told me they didn’t do it. When I would look at the work itself, I would question them, “How did you come about this?” And if they didn’t have an answer, or, often they would say, “I just came up with it.” I would explain that is one way of doing this. But you can’t rely on that every single time, because in graphic design, we have deadlines.

And unlike a studio practice, in graphic design, you must meet the client’s needs. In a studio, I get to make all the calls, and then hope someone really likes it when I put the work out in public. Whereas in graphic design, it’s all about communication.

Sometimes in these one on ones, we would butt heads and the student would argue, “No, I really like my concept,” or, “I’m just trying to do what you are telling me to do.” Then we would put it out to the classroom for critique. Many times, the students would reiterate my concerns. And I always made a point to say, “This is crucial to our understanding of what is it that we are creating? We have it in our own minds that we have answered the questions from The Brief, but when you put it out to the public at large and they say, “What is this? I don’t get it?” you need to do something entirely different.

ENGAGING THE STUDENT

K: This can be frustrating to some students, but that would happen more for the students who were just skating the surface. They aren’t diving deeper into the process. And so they lack the comprehensive understanding of the process to reach the goal of a design. That’s where I would always try to tease this out by asking, “Where did you fall short on this?” And they would reply, “Well, I didn’t do the research.” “Okay, so go back and do the research. Where are your concepts? How many thumbnails did you do?” And they would show me a page of only four or five. “Now spend fifteen minutes and do forty or fifty and see what happens.” A lightbulb would always go off for them. They could see the process of how you concretize those ideas that are just rattling around between your ears.

I always found this to be the most engaging part of the teaching process, no matter what course it was.

Introducing Seniors @ Weizenblatt Gallery reception for Senior Exhibition

You were a conduit for them.

K: I always considered myself the pointer. I am pointing them in a direction, or sometimes, multiple directions. I always told my students that the burden of an education is on their shoulders, not mine. I can sit up here and be a talking head for an entire semester, but you won’t learn anything. If you aren’t engaged with this process, then you are missing out.

And where do the technological tools used in design today fall in your students’ processes? Back in the 80s, everything was done by hand. Now, if you are learning to create concepts, I can imagine the computer to be a distraction or hinderance to the process.

K: Even in my most recent spring semester. I wouldn’t allow students to touch the computer until they went through the process of The Brief. Because the computer is an unlimited, multi-dimensional tool, you can lose your way. Like the enticing calls of sirens, the voices of the cool features in the software overtake the concept of the design.

One of the best projects I would assign in Graphic Design I, at the end of the semester after learning Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, and InDesign, they would have to design a book cover, print it out, and make it fit on an actual book. I created dimensions that would require them to have to tile the images. That means they would have to print a minimum of four sheets, score them, cut them, and put them together. For many of them it was like tearing their hair out and they would say, “This is so difficult!” So we would review all of the steps involved so they wouldn’t waste time skimming over the details and end up with a cover that wouldn’t fit their book. But, strike and set, the majority of my students in the end would have grins on their faces and say, “This is the coolest thing I’ve ever made!”

That lesson not only had all of the tricks and magic of the software, but then it was also hand skills. They built something that was concrete and they could hold in their hand. That was always such a gratifying experience. The end of the semester is a crazy time – so much going on, everyone’s tired. But for me to watch them working together, helping each other cut the pieces, I realized – I don’t even need to be here. They’ve got this. They were fully engaged and owning their learning.

Students and my son working in studio

THE GIFTS OF LEARNING

What is the most gratifying thing about formal education?

K: No artists needs a degree. You don’t need a degree to exhibit your work in a gallery. You don’t need a degree to be a graphic designer. But to me, a degree takes you to a crossroads of so many ideas and categories of different departments, whether it’s history, literature, and so on. It all comes together to form this incredible opportunity. And what a fantastic four years that can be.