An artist’s journey is as unique as their life path, education and collection of experiences. But they do not create in a vacuum. They are influenced by artists that have created before them, mentors that have showed them the way, and colleagues that have shared the pains that always can be found at the beginning of mastering anything. Join us here, as Kenn shares how he began as an artist, how a formal education shaped his work, and how he will never stop learning.

CONVERSATION.09

READY TO BEGIN

How did your formal art education begin?

K: My education truly began in its most formalist sense at the age of 28 when I enrolled in the graphic design program at Louisiana Tech. I turned back to school after dropping out of architecture and working odd jobs for a number of years.

What drove you to go back to finish your education?

K: I realized I needed an occupation for financial stability.

Was it ever a question that it would be in something other than the arts?

K: Never. I always knew I would have an art career. I began with architecture because my father suggested it as a practical occupation, but it never deeply resonated with me. But it seemed like the logical choice because I had taken two years of drafting in high school, and my work stood out among the others. I could draw well. I could also understand three-dimensionality on a flat surface. And then in my senior year, instead of taking a drafting class, I would go to work at the aluminum plant. I would get credit for the class, but would also be paid. So it just made sense.

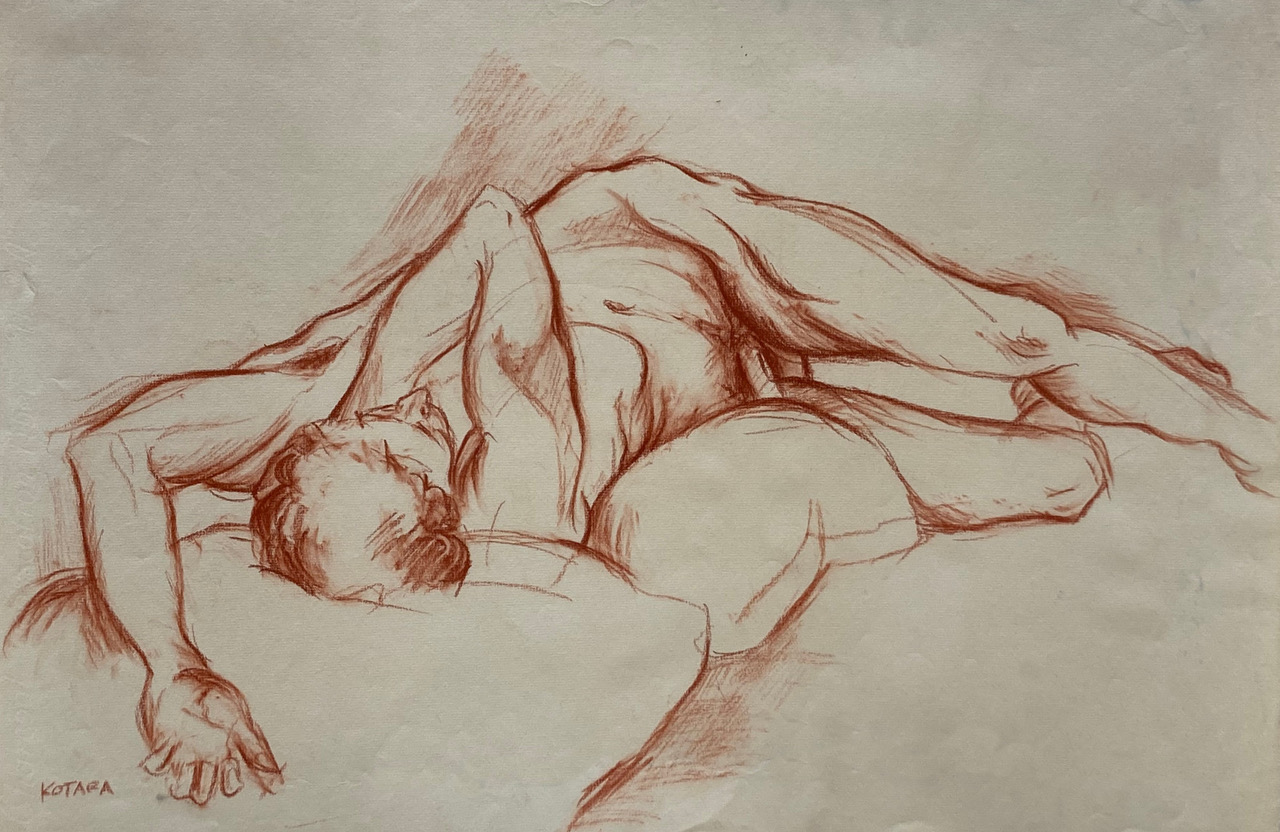

untitled figure

1992, red chalk on paper

But after some time in the program, I realized it did not work for me. I found it too stifling and lacking in creativity. That was my own perception at the time, of course.

CHOOSING A FOCUS

So what moved you then to choose graphic design?

K: I didn’t even know about graphic design until one of my architecture professors recognized I wasn’t intensely interested in architecture. He had seen a caricature I had drawn of the chair of the architecture department, so asked me one day if I had ever considered studying graphic design.

Once I learned more about it, when I came back to school at 28, I knew this was something I could do. Since it also encompassed illustration, it seemed like the perfect fit. Painting and drawing as an illustrator would give me more time to do what I really loved. And, coming back to school at a more mature age, I was really ready to focus.

Upon enrolling in my first ever drawing class, I knew I had landed right where I was suppose to be. So this was the true beginning of my formal, adult education. I realized then, that education was more than just a surface, a title. At that time, I was able to fully understand the power of learning and see the depth it had to it. It was at this time that my work and my being truly began to expand.

So, two years later I had my degree. By this time I had taken two drawing classes and a painting class. I had no idea what I was doing with painting, really. I was learning so much about color, lights and darks, and all this. So the summer after I graduated, I was still trying to figure out what I was going to do. I was presented with an opportunity. A graduate student in the studio program had resigned that position, so they had an opening. I was asked if I would be interested in pursuing the studio graduate program.

They told me normally we don’t like to have our own students from undergrad. But, since I had been in graphic design and taken very few studio courses, they saw that I had something to learn. The undergrad program was eye-opening, but the graduate program was mind-blowing.

A TASTE OF REALITY

K: I had jumped into the deep end, and had to figure it all out to stay afloat. After my first year, we had our first graduate review. All graduate students, whether in the studio program, sculpture, interior design, architecture, would take over the gallery space. All of the faculty would be there. The critiques would go on for three nights. Each person would talk about their work. It was so intense.

peach orchard, spring

1994, oil on canvas

untitled still life

1992

And, how did yours go?

K: They ripped me to shreds. This was only about six months into the program. They basically said I really didn’t know how to paint. They said I had some certain skill sets, but would point things out like, “look at this hard edge you placed on the figure. It draws your attention there. The relationship between that edge and the background doesn’t work.” This all made sense, but at the same time, they were lambasting me.

So after that night, I went home and drank through my miseries. My graduate advisor called at like 7 o’clock the next morning. Of course, I had stayed up late wallowing in my sorrows, and he said, “Be in my office at 8 o’clock.”

So I jumped in the shower. I get to his office, and was probably still wreaking of beer. He says, “Sit down.” and slides a cup of coffee my way. “It was pretty rough last night, wasn’t it?” “Yes, indeed,” I said. And, then at the end, he said, “Here’s what I want you to do.” And to this day, it’s the best advice anyone has ever given me. “I want you to start drawing and painting to fail. I’m not talking about grades. You have lived in a certain comfort zone of painting and drawing in a way that you know. Now I want you to push it. And, I want you to fail. But first, take a week off. Get out of here for a while.”

QUESTIONING EVERYTHING

K: So, we had had this long discussion, and I thought, “What a very wise person.” This changed my whole psyche, my approach, and practice. Later on in my studies, he revealed to me that they had seen great potential in me, but that I also thought I knew everything. “This happens a lot. We all come into this thinking we know how this is suppose to be. But once you do this, you are no longer open to those possibilities. Do you push the paint this way? Does the line quality continue, or do you need to stop it and go another direction? Do you need to add something else to this? Do you need to subtract from it?”

This shift began that idea of questioning for me, every single mark. And, the idea of mark-making was huge back in the early 90s. So that opened up the possibilities, even beyond representational work. They tried to get me to do abstract pieces, where we would create these collages. And then, those collages would be the impetus for a larger piece. But at this time, I was only going through the motions to basically appease my faculty.

DIPPING A TOE INTO THE ABSTRACT

K: But eventually, mark-making expanded my sphere of influence to other artists. This is when I really began to look at the work of Cézanne. He approached everything with a similar mindset. Rock formations, mountains as these 3-dimensional objects, but even his still lifes have a landscape quality. All of his work is about objects placed in foreground, middle ground, and so on. Even his figures are almost like these objects. So it’s almost like, here’s this big landscape, zoom in a little bit closer and here’s a still life, and I’m going to zoom in a little closer and this one object becomes a figure. That for me was one of those “aha moments” of seeing the cohesion of his work. The subject matter changes, but there’s still a continuity there. Throughout all of his work, his focus is about light, darkness, value and color. And, even the materiality of the paint, the slow build up causes refractions of light from a particular light source.

From there, I finally began to move further and further from representationalism. Through graduate school, though, my work was still embedded in representation. Even my graduate show was about landscape, figure and still lifes.

LIFT-OFF

K: Once I graduated and was on my own, there were no questions to be answered by a secondary voice, like that of the faculty. The voice became my own. And then, the question was, “What do I do today?” This launched me into yet another learning phase.

Was there a process of unhearing those faculty voices?

K: {big laugh} Yes! That’s such a great question because for years, you’re tethered to that relationship, and then suddenly you’re given a diploma. They say, “Nice knowing you. Best to you,” and then you’re off. But for the longest time, I could still hear them with me in my studio. Their names and faces still pop up. But, I think that’s what good teaching is about. Those are those mentors whose voices remain with you for life. I remember when I moved to Austin Texas, and was painting landscapes. Even though I wasn’t in the studio at Louisiana Tech, those same voices were still rolling around my head.

You have talked about ‘standing on the shoulders of giants.’ There’s value in taking other people’s learnings with you, but what was your process of finding your own voice through your own inquiry?

K: The process is that it’s a matter of gaining confidence of going to work every day, and working through that. Eventually, the voices become less, your voice becomes stronger, and that’s the way it should be. And that portends that growth.

TO SEE AND BE SEEN

With formal training, is there a set of questions, criteria that a piece must meet (line quality, composition, etc.). Is this what you take from a formal education?

K: In the book, Why Art Cannot Be Taught, James Elkins writes about that entire process, and asks, “What are we teaching? And, are we actually teaching someone?” But as a student participating in the critiques, where, not only do you have your professor objectifying and subjectifying your work, you have your peers doing the same. Having that feedback is so crucial at that formalistic level.

Are you being taught how to see?

K: Well, I think we claim that we are teaching people how to see, but oftentimes what we are actually doing is teaching people what other people see, and how other people interpret your work.

Does that help you shed blinders that you might be wearing? Like, at your first critique in graduate school where you thought you knew everything?

K: Yes, if you’re open to the process. You also realize though, that oftentimes, someone else’s critique, whether it’s positive or not, is an opinion. But, it can be very profound. So if you take it for whatever it’s worth, that’s learning. What I learned through that process was once I create a piece and put it out in public, it’s really no longer mine. If they dislike it, you know immediately. If they like it, it can take on its own life form. Probably one of the most famous examples of that is the Mona Lisa.

The idea of outside influences is a major part of that educational process. And, as a young artist I think it’s crucial to have a circle of like-minded people who understand the language, processes, materials, and so on, so you can have these conversations. And if someone doesn’t like your work, you are not getting mad about it, you are learning. They might ask, “Well, why did you do this? Why did you put this hard edge right here, where everything else is nice, flowing brushwork?” Sometimes we get caught up in our own parameters and comfort zones, and having these outside perspectives helps disrupt this, and broaden our perspective.

When you listen as an artist, are you constantly weeding through what is authentically wanting to come through, verses what you think “should” be there, or appeasing any of the extrinsically motivated notions? Did your art education help you develop your own voice? Did you have to fight for wanting something to be when you were hearing all of this formal critique of it? What happens to you, your work in art school?

K: Typically, it’s the proverbial journey. I would not be where I am without my formal education. I am grateful for it pretty much every day that I work. Simultaneously, I don’t just want to be defined by this as well. But my education started me at a focal point, like in one point perspective. And, I’m moving from that point outward as I grow as an artist.

GAINING NEW PERSPECTIVE

And, you’ve talked about being more open now to folk art or outsider art. Can you use that form of art and compare it to that of a formally educated artist?

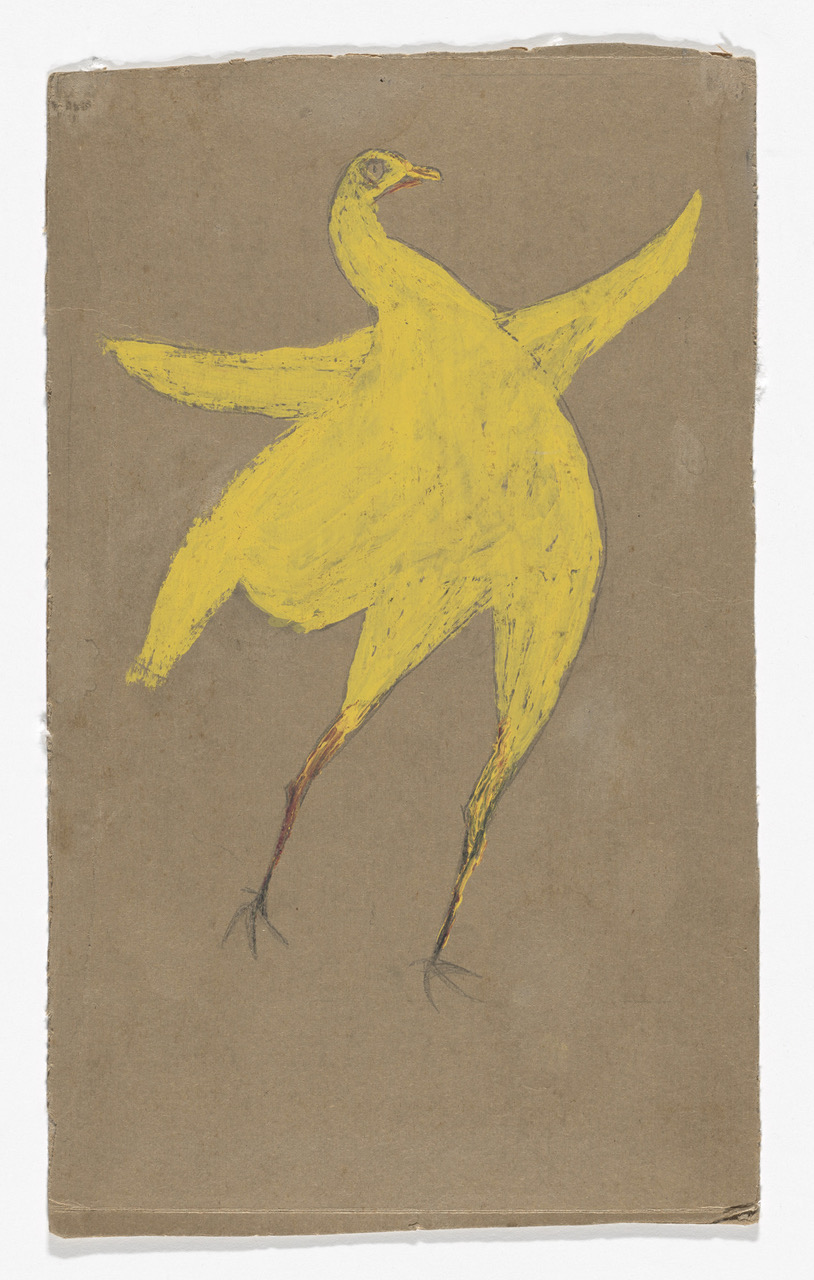

K: When I saw a Bill Traylor exhibition in Washington D.C. a few years ago, I marveled at the expressiveness in his choice of mark making, the symbolism, the imagery and figuration that he was created just on pieces of cardboard. I got lost in his work, and by removing myself from the slickness or formality of my education, just wonder at the materials he was using. Materials don’t have to be a finely stretched canvas, expensive brushed and oils. After that exhibit, I asked myself, ”What can undo in my own formalist education to see what I’m doing differently?”

Bill Traylor, Yellow Chicken, c. 1939-40, gouache & pencil on board, collection MOMA

Would you agree, that outsider artists may have more permission (without even realizing it) to create. It seems like in a formal learning environment, you have all the masters in the room. Is there expectation? How do you cultivate innovation in a formal setting? Where outsider artists may struggle with composition, or they may not know the quality of what they are doing, but sometimes their voice is very strong.

K: That voice for them is everything.

PERMISSION GRANTED

How do you navigate that in a formal environment?

K: In the past couple of years, I now rely more on intuition, then I do with logical objectivity of relations among the elements. Oftentimes before, I would see that if this shape is in this form, color and value, what’s going to be its relation to the next shape. Since I’ve begun to use intuition to guide the work, it allows anything to surface or pop up. Like that idea of pareidolia: of reconstructing data to something that fits our own experiences. I have opened up a whole new breadth to my work, where in the past, I had closed the door saying, “No, I can’t do that.” It has led me to new areas, and also back to essences of figuration. When I revisit some of the Austin landscapes I painted with a perspective from above, I now almost begin to see an image of a bird or a fish. I can then look at my current work and ask, “What else is underneath this surface tension of what I’m creating?” This process is still developing, and in a way, what a great metaphor of allowing myself to go deeper.

the silo

1995, oil on canvas, 70×45 inches

bang bang

2020, mixed media on canvas and wood, 38×50 inches. Private collection, Florida

AND THE LEARNING NEVER STOPS

I would imagine some of the formal techniques of painting, and even training your eye are like motor engrams, ingrained within you – which can be helpful because you don’t have to think about them while creating. For example, if I were to give you a giant canvas right now, and say, “With minimal brush strokes, create a composition.” I bet that within under a minute, you would have a satisfying painting.

K: Well, you touch upon something. I think that one benchmark of change away from my formalist education was when I converted from oil painting to acrylic. It was a different language, because that material is completely different. It still comes out buttery, but oil takes so much longer to dry.

Why did you switch mediums?

K: Because my process, my practice had changed. I had moved into these geometric landscapes. I would get frustrated because I wanted to layer and do these washes, but it would take a week or two to set up and dry where I could paint on top of them again. I wanted to create transparent layers on top of one another.

If you have to set something aside for too long, when you are working with an idea, does that interrupt your flow, or can you sometimes lost that train of thought?

K: Yes. I wanted to expedite, or at least hang on to that idea. So when I switched to acrylic I had to ask new questions. In my formal education working with oils, we learned why every step was so critical: from when stretching the canvas, then prepping the canvas using the old rabbit skin glue (which now we have the gesso that is ready-made) which has to be a particular way or you can ruin a stretcher bar. And then, if your stretcher bars are not taut enough, you can actually contort them. Because when you put wet on dry and then it dries up, it has a great force to it. Then, you start slowly with a mixture of linseed oil, turpentine, and oil paint. In oil painting, you want to paint thin to thick so the paint does not dry out and crack.

Acrylic doesn’t necessarily need this. I now even paint with acrylic onto raw canvas. There’s no laying required. I prefer building it up this way. The canvas soaks up that pigment quite readily, and it has a completely different feel. So, I have gradually gotten away from those external voices telling me what to do, and where my voice becomes confident enough to put this forward. Of course, there’s always self-doubt in there when you’re working on something.

so flows the current (progress image)

2021, mixed media on canvas, 8 x 24 ft. Collection Trammell Crow Company, Atlanta, GA

THAT OLD FRIEND, DOUBT

That is surprising to hear, given your years of experience. I expected the doubt would have faded away.

K: Each day is different. Sometimes the doubt is almost crippling to the point where I don’t even go in to the studio. I’ll change it up and go for a hike or a bike ride. And sometimes the ego will take over and it will say, “This work is so good, it’s so genius.” But it all comes back into the middle.

I would imagine a formal education would be helpful in those moments. To have that objectivity.

K: Not necessarily. The key of Cézannian doubt is well-known. He was so slow and methodical when he painted. Oftentimes people viewed that as he was doubting his next move. Maurice Denis spent a day with him. Upon returning to Paris everyone wanted to know, “What did he say? What did he do?” And Maurice replied, “For the whole day he said very little, and he painted very little.” He would stand there, often, just staring.

Ah, that’s the listening we’ve been talking about.

K: Yes. He was looking, looking doubting, and then now he could make the move. He’d put a dob of paint, and then he’d step back again.

Paul Cezanne, circa 1906

MAKE IT YOUR OWN, BUT NEVER FORGET

K: Formalist training positions you at a jump-off point. Eventually you have to leave that. You don’t negate it, but what you’re striving for is your own voice. I never really liked that term, “voice.” To me, it’s really about your own practice, your own vision. But I have said, I wouldn’t be where I am today without my education. I happened to land at a university where there some faculty members whom I still highly respect. Ed Pinkston, Peter Jones – two incredible artist, but in very different ways. Where Pinkston was very logic and critical thinking about mark making, and the questioning of it. And Jones was a painter, so knowledgeable about so many artists. I am a child of both of their mindsets. There were others too, but they were the giants for me.

Edwin Pinkston, Cloudsplitter

Peter Jones, Conch shell

For the longest time, I considered myself looking up to them. Now, I feel I am on par with them. You can never get away from the student-teacher relationship, but now that I have done this for several decades, it’s like they’re doing their thing, and I’m doing mine.

A LASTING BOND

Do they know of your career, your work?

K: Yes. I still maintain contact with them. I’ll look them up when I’m in Louisiana. That’s always a really nice engagement. We talk about what we’re working on. And of course now, with social media we can keep up in real time with what we are all doing.

Are they still creating?

K: Yes. They’re retired now. I will have a chance to see one of them when I go there for my show in October. They both are still a wealth of information for me. So the learning will always be there.