NYC Summer 2021, Part 1: “Cezanne Drawing” at Museum of Modern Art

Paul Cezanne told the artist Émile Bernard that art required two things – “the eye for the vision of nature and the brain for the logic of organized sensations.”

Plaster cupid, 1900-04, pencil & watercolor on paper, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

The current exhibition of “Cezanne Drawing” at MOMA provides an opportunity to experience the French artist from Aix-en-Provence and his organized sensations in over 250 pencil drawings and watercolor on paper. The quantity along with knowing these works on paper are light-sensitive and usually resigned to climate-controlled vaults is in itself a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

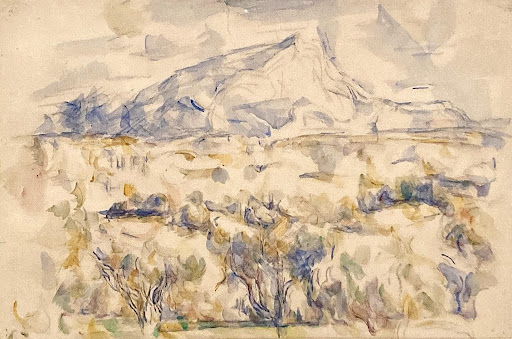

Montaigne Saint Victoire, 1902-06, pencil & watercolor on paper, Tate Museum

Having seen very few of his watercolors, I made the pilgrimage to NYC to view the exhibition. Spread across nine galleries, the drawings and watercolors of figures, still-life and landscapes were almost overwhelming. While MOMA receives credit for producing a prodigious blockbuster exhibit at the quantitative level, Cezanne entices the viewer through a qualitative exercise – the value of slowing time to a near stop.

The jewels of the exhibition are the watercolors – radiant, light-filled veils of color. Cezanne’s organizing approach to what he saw was a slow exercise through attentive observation. He layered color on top of color, working slowly allowing each brushstroke to dry building form, creating space. Distinct color marks or patches can be discerned from one another elucidating his logical process. The even more elegant or interesting works on paper were the “unfinished” or “non finito” sheets. These particular works leave negative space or untouched areas of white to illustrate an object or area within the composition. A radical approach back then.

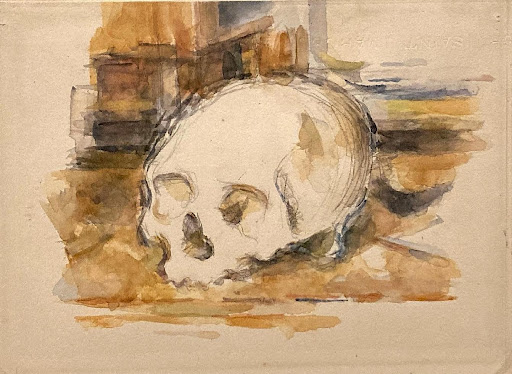

Skull on a table, 1885, pencil & watercolor on paper, Collection Jasper Johns

What Cezanne accomplishes in several watercolor works is an optical illusion of some white areas being whiter than others. Plaster cupid and Skull attain this effect seemingly by bordering the plaster form through his wavering pencil lines and minimal watercolor surrounding the object. There is no added white to the paper – this is the watercolor purist at his best. His uncompromising eye knew the stopping point.

A grouping of 10 rock watercolors exhibited his aesthetic best as they shimmer with movement toward abstraction. Horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines juxtapose with biomorphic shapes in Rocks near the cave above Chateau Noir. Here, Cezanne interrogates weighty geological formations into an airy and light-filled composition. Watercolor daubs of ochre, blues, and greens push and pull the paper’s surface toward and away from us in a dichotomy of flat and real space. His influence in these works toward spatial intelligence leaves little doubt as to his title, “the father of modern art.”

Rocks near the caves above Chateau Noir, 1895-1901, pencil & watercolor on paper, Museum of Modern Art

I spent almost three hours gazing, analyzing, and relishing these works on paper and a few oil paintings, in two runs throughout the course of a single day. Having studied his work in graduate school over 30 years ago, his work upended my traditional way of seeing and thinking.

Viewing this timeless work, was an opportunity to see through Cezanne’s eyes as a witness and intimate observer of the logic of his organized sensations.

Cezanne Drawing, Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 6 – September 25, 2021