NYC Summer 2021, Part 2 – Process, material and evolution: Neel, Mehretu and Benglis

My earliest artworks began via mimesis – copying the masters who imitated nature. Graduate school began a transitional period from realism to abstraction. Influenced by geometry, system structures, and language my work after graduate school continued on the abstraction path to conceptual art.

A week in NYC provided a serendipitous opportunity to view solo exhibitions by Alice Neel, Julie Mehretu and Lynda Benglis. These artists represent a lineage of artistic discoveries and production paralleling my artistic journey and eventual studio practice. I viewed and spent extensive time with the work of these artists relevant to my personal evolution.

A survey of Alice Neel’s figurative paintings of family, friends, and lovers titled “People come First” at The Metropolitan Museum depicts striking portraits conveying an immediacy of line and color at first glance. Vibrant. Intimate. A longer look reveals an intense psychological relationship emerging between sitter and artist. Neel lays down just enough paint, as emotional evidence, to capture the tension and essence of her subjects. In Andy Warhol, Neel renders the face, torso, and shoes with recognizable clarity. She allows a few lines and background color to float within the substrate’s flatness. She is at her best when using less. Few subjects appear comfortable as if Neel is extracting more than the image. She demanded much from her sitters and herself, and for that, one critic called her a “collector of souls.”

Alice Neel, Andy Warhol, 1970, Whitney Museum of American Art

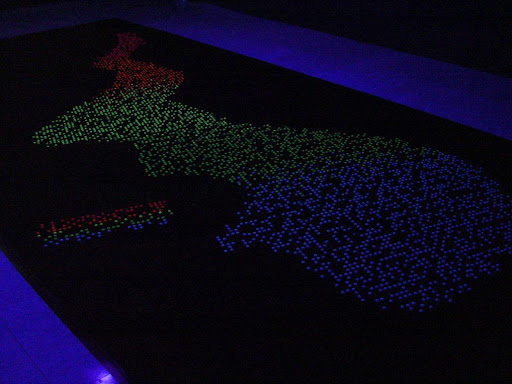

Julie Mehretu systematizes abstract paintings, drawings, and prints based on sociopolitical change, architecture, and literature. Two concurrent exhibitions – Whitney Museum of American Art and Gemini G.E.L. offer viewers much to take in. Her large-scale paintings at the Whitney present complex layers of information, articulating societal interests in incessant consumerism and connectivity. Dense accumulations of exacting linear drawing, geometric shapes, and expressive mark-making create a dichotomy of flat versus depth. The smaller exhibit at Gemini offers an intimate setting with prints created since 2008. Here Merhetu is at her best – a vision of energy and forces captured at its brightest moment on a flat surface.

Julie Mehretu, Untitled, 2008, dry point, Private Collection

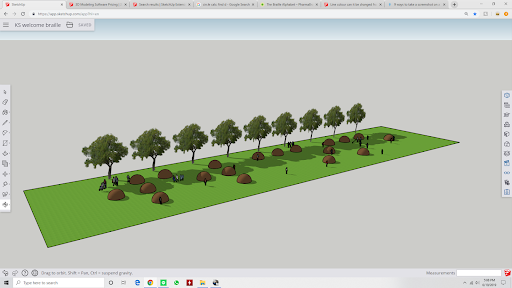

Lynda Benglis rounds out my evolutionary review with large cast bronze sculptures in “An Alphabet of Forms” at Pace Gallery. Benglis continues to inspire me as an artist. Not just that we both originate from Lake Charles, Louisiana, but most impressive and intriguing are her early poured latex works. These fluid works, realized on floors, redefined painting in the 1960s. “An Alphabet of Forms” continues her interest in forms and material exploration as liquidity. Each “knot-like” naissance is a smaller clay sculpture which is then digitally enlarged. The sculptural forms simultaneously adhere to and evade gravity in their own sculptural entanglement. They appear dropped from above and placed precisely. Viewers circumnavigate the sculptures in a causal dance associated with material, matter, and memory.

Gallery Installation, 2021, Pace Gallery, NYC